Written By: Rameez Makhdoomi

India is a melting pot of civilizations, a home to the largest number of languages, ethnicities, and cultures in the world. Amid this immense diversity, Kashmir stands out as a civilizational jewel, a land where philosophy, mysticism, and poetry converged to create one of the subcontinent’s most refined spiritual temperaments. Yet, despite its ancient Sufi-Rishi ethos, Kashmir has remained a deeply troubled region, politically unsettled and socially fractured.

In recent years, however, there has been a visible improvement on the ground. Levels of violence have declined, and terror incidents have seen a sharp fall. Apart from isolated tragedies like the Pahalgam attack, the overall situation appears calmer than it has been in decades. Yet, beneath this calm lies a more complex challenge, the need to cement the idea of India in a way that transcends tokenism and political performance. Simply unfurling flags, holding cultural events, or delivering speeches are not enough to create belonging or conviction. The real task is to nurture a civilization ethos that resonates with the moral depth and cultural continuity of the region.

In this era of “might is right” and moral erosion, what Kashmir needs is not just peace through policing but peace through principles, a civic and cultural renewal that stands above partisan politics. The focus must be on cultivating Kashmiris who are loyal to the broader ethos of India, not merely to the government of the day. What we need are critical Indians, citizens unafraid to ask questions, who think deeply about the environment, economy, education, and justice, yet hold an unshakable affection for their nation.

The idea of coexistence has always been embedded in Kashmir’s soil, through the verses of Lal Ded, the teachings of Nund Rishi, the wisdom of Abhinavagupta, and the countless shrines and temples that once stood side by side. What is needed today is a reawakening of these civilizational resources. We must shift from narrow “de-radicalization” programs to cultivating re-humanization, teaching the next generation of Kashmiris the values of empathy, pluralism, and shared destiny.

Schools, colleges, and universities must become sites of moral imagination, not only teaching technical knowledge but also cultural wisdom. Kashmir’s young deserve to learn that coexistence is not weakness; it is the very strength that once defined their ancestors. Holding conferences, creating grassroots dialogues, and reviving local histories of harmony are essential. The Sufi and Rishi icons of Kashmir offer abundant teachings on compassion, humility, and service. Even contemporary Islamic scholars rooted in the region’s syncretic ethos emphasize tolerance and peaceful coexistence.

It is distressing that most schools, even elite ones, have almost zero focus on these moral foundations. They prepare students for careers, not for citizenship. The real education for peace begins not in seminar halls but in daily life, in shared classrooms, interfaith debates, and community initiatives that remind the young that their humanity precedes all religious or political labels.

To cement lasting peace and prosperity, we must move beyond optics and focus on emotional integration. Institutions of education, culture, and religion must work together to cultivate a sense of belonging among Kashmiris. Local communities need to engage in cultural exchange, interfaith dialogues, and collective acts of service, planting trees together, rebuilding schools, organizing health camps, because peace grows through shared action, not rhetoric.

We must also correct a crucial misconception: the idea that being “Indian” in Kashmir is confined to a small, vocal minority. In truth, the vast majority of Kashmiris live their Indian identity quietly, through everyday acts of resilience, work, and love for their land. The few who harbor hostility or skepticism toward India are often the products of trauma, disillusionment, or misrepresentation over the past four decades. It is time to reach the next generation not with suspicion or force, but with the weapons of respect, dialogue, and moral conviction.

A truly healed Kashmir will emerge not when slogans drown the air, but when hearts resonate with the simple conviction that to be Kashmiri and to be Indian are not contradictions but continuities.

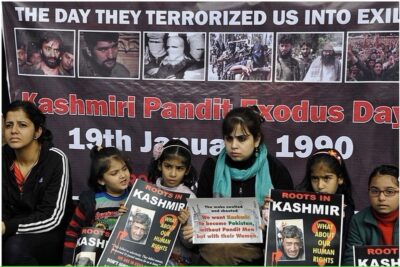

However, no vision of coexistence or civilizational renewal can be complete without confronting the deepest wound in Kashmir’s modern history, the forced exodus of Kashmiri Pandits in the early 1990s. This tragedy was not only a demographic or political upheaval; it was the moral dislocation of an entire civilization.

Kashmir, for centuries, had stood as a remarkable crossroads, where Shaivite mystics and Sufi saints shared vocabularies of transcendence, where temples and shrines existed in proximity, where music, art, and language reflected plural inheritance. The exodus of Pandits ruptured this moral geography. It marked not only the displacement of a community but the unmaking of the Valley’s very soul.

The inability to bring them back, even after three decades, stands as a painful reminder of the distance between rhetoric and reality. Despite numerous government initiatives, housing colonies, employment packages, scholarships, and token gestures of inclusion, the essence of rehabilitation remains unfulfilled. Rehabilitation is not about returning people to houses; it is about returning them to belonging.

The tragedy of the Pandits carries a double betrayal, first, in their forced displacement; and second, in their non-rehabilitation. The exodus rendered them exiles in their own homeland, and the prolonged inaction of both state and society deepened their alienation.

Over time, what was once a shared moral failure has been turned into a political symbol. Different political actors, across parties and ideologies, have appropriated the pain of Pandits for their own narratives. In the process, the human core of the tragedy was lost. Pandits became not participants in the Valley’s story but subjects of its politics.

Even well-meaning policies have often missed the point. Job reservations or fenced “Pandit colonies” risk creating new forms of segregation. These are administrative shelters, not homes of the heart. To fence a community in the name of protection is to confine its spirit. The idea of rehabilitation must, therefore, move beyond the transactional and become transformational, rebuilding the moral ecology that once made coexistence organic.

Calls to “bring Pandits back” often overlook the deeper transformation of Kashmiri society. The social fabric of the early 20th century, where Muslims and Pandits shared food, grief, and festivals, has thinned with time. The generation that remembered those relationships has either passed away or migrated. To ask Pandits to return without reconstructing the ecosystem of trust is to invite them into emotional exile. They may return to their land, but not to life.

Moreover, the Valley today hosts both hopeful and hostile elements. While many young Kashmiris yearn for reconciliation, some ideologues continue to nurture narratives of division. The task, therefore, is not merely logistical, it is moral and pedagogical. The ground must be made fertile again for coexistence through patient re-education, honest dialogue, and local ownership of the reconciliation process.

True rehabilitation must begin with acknowledgment, a recognition that the exodus was a collective wound. The loss was not one community’s alone; it diminished every Kashmiri. The Pandits’ absence is felt not only in abandoned temples but in the silence of cultural spaces, the absence of teachers, doctors, and civil servants who once shaped the Valley’s intellectual life.

This acknowledgment must not arise from guilt but from shared responsibility. The first step toward reconciliation is to accept that what happened was a tragedy, not in a partisan sense, but in a human one. Civil society, local scholars, imams, teachers, and journalists must lead this moral reconstruction. Governments can build walls and offer jobs, but only communities can rebuild trust.

Rehabilitation cannot mean isolation. The idea of creating separate Pandit colonies contradicts the very ethos of shared living. The goal must be integration, shared neighbourhoods, common institutions, mixed schools, and cooperative local bodies where trust grows through proximity. Rehabilitation is not about “returning Pandits” but about restoring community.

At the same time, the Pandit community itself must be seen not merely as victims or beneficiaries but as participants in rebuilding Kashmir’s moral and intellectual landscape. Their memories, art, and lived experiences must be reintegrated into the collective consciousness. When a Pandit teacher returns to a school, or a doctor serves in a Valley hospital, or a poet’s words are recited again in a local festival, that is the true rehabilitation, quiet, lived, and human.

The greatest tragedy of the post-exodus years was that the word “Kashmiri” became divided by hyphens: Muslim, Pandit, Shia, Sunni. The shared sense of belonging was lost. The task ahead is to reclaim “Kashmiri” as the primary identity, transcending sectarian and political labels.

Every Kashmiri, regardless of religion, must see the return of the Pandits as integral to their own moral healing. When Pandits return, it should not be seen as a political concession or a demographic balancing act, but as the completion of Kashmir’s soul. The Pandit is not an outsider; they are an essential thread in the Valley’s cultural fabric, a teacher, a neighbour, a poet, a bureaucrat. The image of a Pandit woman contesting local elections or a Pandit youth teaching at Kashmir University should become ordinary, not exceptional.

Governments can only create frameworks; societies must create harmony. The real work of reconciliation lies in civil society, in teachers, artists, local clerics, and community elders. The mosques, temples, schools, and community centres must once again become sites of shared dialogue and service. When Muslims and Pandits together rebuild a school, clean a shrine, or organize a cultural festival, they revive the invisible threads that once bound them.

Universities in Kashmir should also play a leading role by setting up centres for peacebuilding, memory studies, and inter-community dialogue. Scholarship should become a means of healing, and education a means of reconciliation. Religious leaders, too, bear moral responsibility. The spiritual idioms of Lal Ded and Sheikh-ul-Alam, of compassion and shared humanity, can once again become guiding lights.

The road to genuine rehabilitation is long, but not impossible. It requires courage, moral and emotional, to confront the wounds of history without weaponizing them. It requires humility to listen to each other’s pain, and patience to rebuild trust through small, consistent gestures.

The future of Kashmir will not be defined by military calm or political speeches, but by whether its people can once again live together without fear, prejudice, or memory of betrayal. The true triumph will be when a Pandit family, a Sikh family, and a Muslim family share tea in the same courtyard, speaking not of separation but of shared tomorrows.

To be Indian in Kashmir, then, must not mean shouting one’s allegiance. It must emerge from within, as a civilizational choice, as a moral belonging, as a cultural rhythm. The call of being Indian must flow naturally from the call of being Kashmiri.

When that day arrives, when the Valley breathes again as one moral community, when coexistence replaces suspicion, and when Pandits and Muslims together rebuild the dream of a shared home, only then will Kashmir truly reclaim its civilizational promise.

That will be the moment when the long night of exile ends, not in slogans, but in the quiet warmth of neighbours sharing tea by the Jhelum, remembering without bitterness, and building without fear. That will be the true rehabilitation of Kashmir, not only of a people, but of the Valley’s conscience itself.

To conclude, in this context, any future framework for rehabilitation and coexistence in Kashmir must strongly emphasize the principle of non-refoulement. This means ensuring that no individual or community is compelled or coerced into returning to a situation where their safety, dignity, or freedom might be jeopardized. The return of displaced communities, especially the Kashmiri Pandits, must be grounded in voluntary choice and the assurance of justice, not political symbolism or administrative compulsion. Embedding non-refoulement within the broader framework of reconciliation ensures that rehabilitation becomes a humane and rights-based process, one that reflects India’s constitutional morality and civilizational commitment to compassion and coexistence. It marks a shift from reactive policymaking to an ethical vision that values dignity as the foundation of peace.

The Governments have a pivotal role to play in bridging the emotional and historical void that persists in Kashmir. If genuinely committed to lowering these divides, they can devise a framework that integrates empathy with practicality. Such a framework should be built upon the spirit of compassion, developing platforms that promote sustained and meaningful communication between communities. The emphasis must be on dialogue rather than diktat, listening rather than lecturing. True reconciliation grows from the patience to listen and understand the perspectives of all stakeholders, acknowledging pain without politicizing it.

A collaborative approach is essential, one that encourages diverse voices to co-design solutions, driven by a shared urge to find a path forward rather than win an argument.

The process must move along a cooperative and compromising ladder, where mutual concessions become the building blocks of peace. Above all, resilience of leadership will determine the success of such efforts, the moral strength to uphold resolve even amid setbacks or criticism. Only when compassion shapes governance, patience tempers politics, and cooperation replaces confrontation will Kashmir move from conflict to coexistence.

This is not merely the task of governments, but of every conscience that believes in the power of humanity over history, and dignity over division.