Written BY: Irshad Ahmad ( Research scholar )

Kshemendra (c. 990–1070 CE), an eminent polymath of medieval Kashmir, composed Samaya Mātrikā during the Lohara dynasty, a polity characterised by socio-political heterogeneity, religious pluralism, and the institutional consolidation of Sanskritic epistemic authority. Traditionally translated as The Courtesan’s Keeper, the text follows a courtesan instructing her young ward on dealing with religious institutions and bureaucratic structures rife with corruption. This device transforms the courtesan’s world into an allegorical arena where hypocrisy, exploitation, and moral duplicity are exposed to the public sphere.

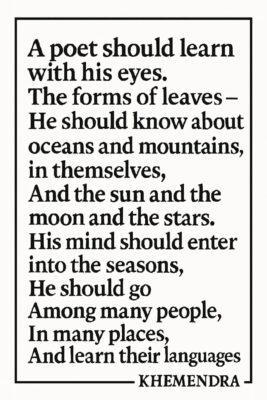

Kshemendra, educated in Vaishnavism, Buddhism, and Vedic traditions, first gained renown for abridging and adapting canonical texts before, after 1037 CE, turning to original compositions when Kashmir was growing as a centre of Sanskrit learning, pilgrimage, and trans-regional trade.In this milieu of intellectual pluralism and changing authority, Samaya Mātrikā employs satire as a mode of public reasoning. By centring on a courtesan and her ward, figures marginal and indispensable to the urban economy. Kshemendra investigates religious authority and commercial and governmental power. The text’s cosmopolitan references to Chinese and Turkish peoples, along with its detailed urban scenes, highlight the porous cultural frontiers of medieval Kashmir.

Kshemendra’s work today explores not only a vivid portrait of Kshemendra’s era but also an early genealogy of civic dissent, moral critique, and imaginative reordering of social life. Scholars such as R.K. Kaul (1993) and A.K. Warder situated Kshemendra’s work within the broader South Asian tradition of didactic and moral literature, while S.N. Dasgupta (1922) holds dear his innovative rhetorical strategy, which transforms satire into a tool for social critique. From a contemporary socio-political perspective, Samaya Mātrikā provides lasting insights into the mechanisms of institutional decay, the perpetuation of social hierarchies, and the moral responsibilities of individuals within complex power structures, making it a valuable resource for understanding both historical and present-day societal dynamics.Rather than treating Samaya Mātrikā as a historical curiosity, this text proposes it as a critical lens for analysing ongoing contradictions in civic life. Like Habermas’s (1989) notion of the public sphere and Scott’s (1990) theory of “hidden transcripts”, Kshemendra’s satire exposes the gap between normative ideals and everyday practices. It further invites a re-examining of the ethical responsibilities of intellectuals and cultural producers, aligning with ideas of Bourdieu’s (1996) call for “reflexive sociology” that turns critique back on its own social conditions. Samaya Mātrikā is often viewed by many noted scholars as “Mother of the Times”. Its characters, especially Kankali the courtesan, embody a society skilled in survival, patronage, and performance.

Kshemendra uses their stories to expose how moral codes are bent to suit convenience, how religion can be weaponised for profit, and how marginalised voices both suffer and subvert the system.

Jammu & Kashmir’s crisis is as much moral as it is socio-political or economic. The erosion of public trust over the past 3 decades due to violence cannot be repaired by infrastructure alone. It requires relearning how to critique power without violence and how to hold ourselves accountable without despair. This is where Kshemendra’s method is potent. Satire, when positioned in empathy, can dismantle hypocrisy without inflaming new divisions. It can speak to power in a register both familiar and disarming. AsSheldon Pollock (2003) situates Sanskrit’s “politics of aesthetics” within a broader South Asian public sphere, suggesting that texts like Samaya Mātrikā enabled nonviolent yet forceful critique.

A region fatigued by sermons and propaganda could use more of this kind of laughter – laughter that reforms rather than ridicules. J&K’s universities, cultural centres and NGOs can adapt Samaya Mātrikā into public performances, graphic novels, or short films, encouraging young writers and artists to learn the craft of critique. Kankali, the courtesan-protagonist, is a figure who is more informed about systems than their official guardians, despite being marginal. It is possible to go beyond victim narratives and initiate fresh discussions about women’s agency, labour, and power negotiation by introducing her to classrooms and workshops. Kshemendra subtly favoured moral faith over meaningless ritual while mocking religious imposters of all kinds. Samaya Mātrikā readings and discussions in public can serve as interfaith forums, reclaiming Kashmir’s syncretic traditions, or what we call Kashmiriyat, and serving as an example of a critique that is non-sectarian but principled.

Kshemendra’s work is a case study for constructive critique of oneself for media outlets, civil-service academies, and community leaders. This would normalise ethical reflection among those who wield influence, helping rebuild the credibility of public institutions.For India as a whole, revisiting Kshemendra is also a reminder that Jammu & Kashmir’s identity is not reducible to its conflict. It has produced world-class literature capable of scrutinising its own society long before modern democratic norms arrived. Emphasising this heritage challenges stereotypes of the Valley as merely a security problem and instead frames it as a crucible of civic thought – a region with an indigenous tradition of holding power to account.

Moreover, in a time when satire is increasingly either trivialised into memes or punished for irreverence, Kshemendra’s example shows a third path: satire as a disciplined, morally rooted, socially constructive practice. It is a skill India’s democracy could use more widely.Bringing Samaya Mātrikā into today’s Kashmir is not about nostalgia but about continuity – connecting a rich past to a fraught present. It would mean commissioning translations in Kashmiri and Urdu, hosting public performances, including it in civic and gender studies and training young creators to adapt it carefully and responsibly. Such initiatives would not replace the hard work of governance, but they would enrich it by nurturing critical, culturally grounded citizens.

Kshemendra’s satire can do what it did in his time: remind society of its own contradictions and its capacity to transcend them. Nine hundred years ago, Kshemendra diagnosed his society’s ills with wit sharper than any sword. It is prepared to serve as a mirror in the face of polarisation and multiple front challenges in Jammu & Kashmir today—not to embarrass, but to awaken. It challenges us to examine our delusions, laugh at our hypocrisies, and re-establish public confidence based on moral rectitude and honesty.

If we take up that invitation, we may find in Kshemendra not just a poet of the past but an ally for the future – a Kashmiri voice reminding India that the best way to heal a divided society is to see it clearly, speak of it bravely, and, when needed, laugh ourselves into reform.Revisiting Kshemendra’s Samaya Mātrikā contributes to two debates: first, the reconsideration of premodern South Asian texts as resources for understanding modernity’s discontents (Chakrabarty, 2000); and second, the role of literary satire as a mode of civic renewal and moral imagination (Bergson, 1911; Hutcheon, 1994). Reading Samaya Mātrikā through these theoretical lenses explores that Kshemendra’s work remains salient for imagining more inclusive, accountable, and self-reflexive political cultures in the region today.

References

A. N. D. Haksar (Trans.). (2008). The Courtesan’s Keeper (Samaya Mātrikā). Penguin Classics India.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field (S. Emanuel, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton University Press.

Dasgupta, S. N. (1922). A history of Indian philosophy (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger with F. Lawrence, Trans.). MIT Press.

Pollock, S. (2003). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press.

Kaul, R. K. (1993). Studies in Kshemendra. Motilal Banarsidass.

Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the arts of resistance: Hidden transcripts. Yale University Press.

Warder, A. K. (1990). Indian Kavya literature (Vol. 5). Motilal Banarsidass