By: Kaiser Ahmad Thoker ( Research Scholar)

At the global level, the question of energy conservation is no longer a matter of choice, preference, or technological sophistication; it is a matter of moral survival. The contemporary world has reached a point where it possesses unprecedented scientific knowledge about the consequences of its actions, yet continues to behave as if ignorance were still an excuse. Fossil fuels have powered modern civilization, but they have also quietly rewritten the terms of existence itself. Rising temperatures, melting ice caps, unpredictable weather, disappearing species, and collapsing ecosystems are not unintended side effects; they are the logical outcomes of an economic and political system that treats energy as infinite, nature as expendable, and future generations as politically irrelevant. National Energy Conservation Day, when observed without this global context, risks becoming a hollow ritual – a moment of symbolic concern detached from the structural violence embedded in the global energy order.

The global distribution of energy consumption exposes a deep moral fracture. A small fraction of the world’s population consumes the majority of its energy resources, while billions live with scarcity, uncertainty, and vulnerability. This imbalance is not accidental; it is the result of historical extraction, colonial expansion, and industrial growth that privileged some regions at the expense of others. The Global North built its prosperity by burning fossil fuels on a scale that the planet cannot sustain, and now, having exhausted much of the ecological space, it preaches moderation to the rest of the world. Climate diplomacy is saturated with the language of responsibility, yet carefully avoids the language of accountability. Terms like “net zero,” “carbon neutrality,” and “energy transition” are deployed to create the illusion of action while allowing business as usual to continue under a greener vocabulary. Energy conservation, in this discourse, is deferred, diluted, and domesticated so that it does not threaten entrenched interests.

What makes the global failure on energy conservation particularly disturbing is the deliberate displacement of responsibility. Ordinary citizens are urged to modify behavior, reduce consumption, and feel personally accountable for a crisis driven overwhelmingly by large corporations, militarized states, and elite consumption patterns. While individuals are important moral agents, this framing obscures the reality that systemic energy waste dwarfs personal conservation. A single coal-fired power plant, an arms manufacturing complex, or a network of luxury consumption can negate the conservation efforts of entire communities. Yet these structures remain politically protected. The global economy continues to reward excess, speed, and accumulation, while restraint is portrayed as unrealistic, inconvenient, or even dangerous. In such a world, energy conservation becomes a subversive idea because it challenges the very logic of endless growth.

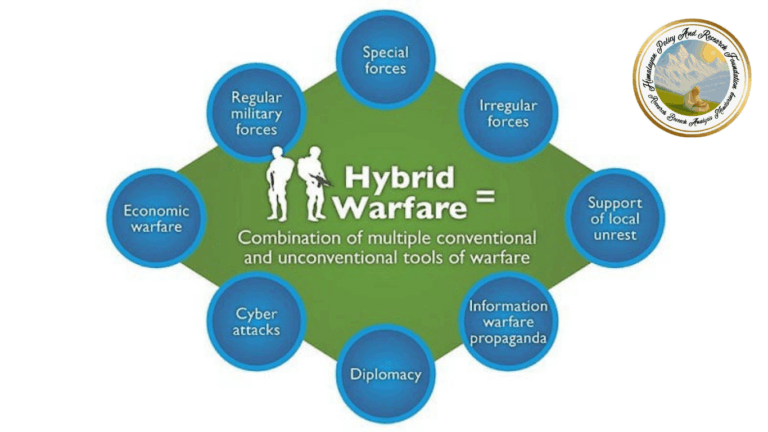

Energy has also become a tool of geopolitical dominance. Wars are fought, alliances are forged, and sanctions are imposed in the name of energy security. Oil and gas pipelines are guarded more fiercely than ecosystems, and extraction is justified as a strategic necessity. Conservation, in this context, is often dismissed as naive idealism, incompatible with national interest. This is a profound distortion. Dependence on fossil fuels has not made the world safer; it has made it more volatile, unequal, and violent. True energy security does not lie in controlling resources, but in reducing dependence on destructive systems. Conservation, decentralization, and renewable energy threaten existing power hierarchies, which is why they are resisted with such determination.

National Energy Conservation Day must therefore be understood not as a celebration of small efficiencies, but as an indictment of global hypocrisy. The science has spoken with brutal clarity, yet political systems continue to negotiate with reality as if compromise were possible. The planet does not respond to speeches, targets, or deadlines chosen for electoral convenience. It responds only to emissions. In this sense, delayed conservation is not caution; it is betrayal. Every year of inaction transfers risk from the present to the future, from the powerful to the powerless, from those who benefit to those who will suffer. To conserve energy today is not to sacrifice comfort; it is to refuse to participate in a lie – the lie that endless consumption on a finite planet is possible.

India occupies a complex and often contradictory position within the global energy debate. As a country with vast developmental needs and a history of colonial exploitation, India rightly emphasizes the principle of climate justice and differentiated responsibility. Yet this legitimate argument is increasingly weakened by internal patterns of inequality, waste, and uncritical imitation of energy-intensive development models. India’s energy problem is not simply one of access; it is one of imagination. The dominant vision of progress remains tied to consumption-heavy urbanization, automobile dependency, concrete expansion, and extractive growth. In this model, conservation appears as an obstacle rather than a necessity, and restraint is framed as deprivation rather than wisdom.

The coexistence of energy poverty and energy excess in India reveals the moral failure of its development trajectory. Millions of households still experience unreliable electricity, dependence on polluting fuels, and vulnerability to price shocks, while a growing urban elite consumes energy at levels comparable to the most affluent societies in the world. Air conditioners run continuously in glass buildings designed without climatic sense, private vehicles multiply despite collapsing urban infrastructure, and digital expansion quietly drives massive energy demand through data centers and networks that remain largely invisible to public scrutiny. Conservation campaigns often target ordinary citizens, urging them to switch off lights or use efficient appliances, while the structural drivers of waste remain untouched. This selective moralization deepens inequality and erodes trust.

India’s continued reliance on coal illustrates this contradiction sharply. Coal is defended as essential for growth and employment, even as its environmental and health costs are borne disproportionately by the poor. Mining displaces communities, power plants pollute air and water, and climate impacts intensify rural distress. Renewable energy, despite its vast potential, is often pursued in a centralized, corporate-driven manner that replicates old patterns of exclusion rather than empowering local communities. Conservation, which could reduce demand and ease transition pressures, remains marginal in policy imagination because it challenges the assumption that development must always mean more – more energy, more extraction, more speed.

Nowhere do these contradictions acquire sharper ecological and political significance than in Kashmir. Often portrayed as a region of natural abundance, Kashmir is in reality a fragile ecological system under severe stress. Climate change has already begun to alter its landscape in irreversible ways. Glaciers are retreating, snowfall is becoming erratic, springs are drying up, and extreme weather events are more frequent. These changes directly affect agriculture, water availability, and livelihoods, yet they rarely shape energy or development policy in a meaningful way. Conservation here is not an abstract environmental ideal; it is a matter of survival.

Despite its hydropower potential, Kashmir experiences chronic electricity shortages, inefficient distribution, and frequent load shedding. Energy abundance is paradoxically converted into scarcity through mismanagement, transmission losses, and centralized control that excludes local participation. Citizens are asked to conserve electricity while infrastructure leaks energy at every stage. This produces not sustainability, but frustration. Conservation imposed without addressing systemic inefficiency becomes another burden on ordinary people rather than a collective project.

Urban expansion in Kashmir reflects the same developmental blindness seen elsewhere. Wetlands that once absorbed floods are encroached upon, concrete replaces permeable land, and vehicular traffic increases in cities not designed for it. Dal Lake, once a living ecosystem, struggles under pollution and neglect. These ecological disruptions intensify energy demand while simultaneously reducing natural resilience. Conservation cannot succeed in isolation from ecological planning; both are being undermined by short-term thinking.

In rural Kashmir, older traditions of moderation, seasonal adaptation, and community stewardship are eroding under the pressure of modern consumption patterns. Yet this transition has not delivered energy security or economic stability. Instead, it has increased dependence, costs, and vulnerability. When conservation is framed only as an individual duty, without addressing governance failures and structural injustice, it feels punitive rather than empowering.

There is also an unmistakable political dimension to energy in Kashmir. Decisions are centralized, transparency is limited, and public participation is minimal. In such a context, energy conservation risks being perceived not as a shared responsibility, but as another directive imposed from above. Sustainable energy futures require trust, inclusion, and local agency – conditions that remain fragile. Without them, conservation becomes a slogan rather than a practice.

National Energy Conservation Day, when viewed from Kashmir, is therefore less a celebration than a warning. A warning that ecological limits are real and unforgiving. A warning that development without restraint erodes the very foundations of life. A warning that energy injustice deepens social and political alienation. Conservation here is not about saving units of electricity; it is about preserving habitability, dignity, and continuity.

Ultimately, energy conservation is not a technical adjustment but a civilizational decision. India must choose whether it will repeat the mistakes of those who came before or imagine a path rooted in restraint, equity, and ecological wisdom. Kashmir must choose whether it will protect its fragile landscape or sacrifice it to cosmetic development. National Energy Conservation Day must confront us with an uncomfortable truth: the cost of inaction will not be paid in abstract numbers, but in disrupted lives, lost livelihoods, and stolen futures.

The real question is no longer whether conservation is feasible.

The real question is whether we possess the moral courage to choose it.