Written by: Irshad Ahmad ( Research Scholar )

In Jammu and Kashmir, winter sports embody a complex intersection of geography, culture, economy, identity, and aspiration that defines the region’s relationship with its distinct winter environment. As such, they are much more than just recreational activities. Centuries of human adaptation to harsh climate conditions have shaped the essence of winter sports in this Himalayan region, and in the current context, they have developed into a potent force for tourism, livelihood creation, youth engagement, and international visibility. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus helps to explain this internalization: people of these mountains develop physical dispositions and an intuitive relationship with snow long before encountering formal skiing. The environment acts as more than just a physical setting; it also becomes a cultural force that shapes attitudes, physical behaviours, and athletic customs. As one of the few regions in country with consistent and prolonged snowfall, Jammu and Kashmir holds a unique position as a winter-sports hub in South Asia. Both recreational adventure and professional competitive sports are supported by the natural platforms created by the snow-covered slopes of Gulmarg, Pahalgam, Sonamarg, and the high-altitude deserts of Ladakh. Examining how natural circumstances, historical and economic factors, and cultural dynamics come together to make J&K a distinctive winter-sport destination is necessary to grasp the essence of winter sports here.

The foundation of winter sports in Jammu and Kashmir lies in its extraordinary geography. The region is located at the convergence of the Pir Panjal Range and the Greater Himalayas, a terrain characterized by steep gradients, wide alpine meadows, deep valleys, frozen lakes, and some of the highest inhabited regions on the planet. These characteristics guarantee the perfect setting for ice climbing, ice skating, ice hockey, snowboarding, snowshoeing, and skiing. Gulmarg’s Apharwat Peak, reaching approximately 4,200 meters, is home to some of the longest ski runs in south Asia and is globally recognised for its powder snow and natural slopes. Long winters lasting from December to March ensure stable snow conditions, which is critical for maintaining a predictable sporting season, something that many other regions in South Asia cannot replicate. The quality of snow, the depth of accumulation, and the natural distribution of slopes across varying difficulty levels, from beginner-friendly meadows to advanced steep drops, form the natural core of why winter sports thrive in Jammu and Kashmir. This environment not only attracts tourists and athletes but also influences the very culture and livelihood patterns of the people living in these high-altitude landscapes. Winter sports in the region also draw from deep historical ties and cultural roots. Local communities had developed strategies for surviving in the harsh winter landscape long before skiing became a recognised sport or a popular tourist destination. In the upper reaches of the Kashmir Valley and the icy plateaus of Ladakh, shepherds, traders, and villagers relied heavily on traditional sledges, homemade wooden skis, and manual snow-clearing methods. These winter practices, although not defined as sports at the time, instilled in the population a familiarity with snow-covered terrain and a respect for the mountains during winter.

The origins of winter sports in Jammu and Kashmir can be located in early twentieth-century colonial expeditions, when explorers and mountaineers identified the region’s biophysical potential for skiing and ice-based mobility. What initially functioned as subsistence and survival practices gradually began to transform into organized winter sport activities. Over subsequent decades, institutions such as the Indian Institute of Skiing and Mountaineering in Gulmarg and the Jawahar Institute of Mountaineering in Pahalgam formalized this evolution by establishing structured training programmes, introducing internationally standardized techniques, and producing technically skilled local youth who later served as instructors, guides, and competitive participants. By embedding winter practices within community identity structures, this institutional progression strengthened the cultural linkage between winter environments, mountain terrains, and sporting traditions. Traces of cultural consolidation is visible in winter festivals, village-level competitions, ice hockey tournaments in Ladakh, and snow-sport workshops across Kashmir, which collectively position winter sports as markers of community cohesion and pride.

Economically, the winter-sport sector has emerged as one of the most significant pillars sustaining the region’s tourism and livelihood system. Given that tourism in Jammu and Kashmir has historically unveiled strong seasonality flourishing in summer but contracting sharply in winter, the expansion of winter sports has reoriented this pattern by generating a robust secondary tourism season that attracts thousands of visitors annually. Winter sports have helped to diversify regional income streams, make seasonal changes less extreme, and boost the overall tourism economy. Gulmarg, in particular, is known around worldwide as a great place to ski, attracting visitors from Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and many parts of India. The Gulmarg Gondola, ranked among the highest aerial ropeway systems globally constitutes a critical infrastructural asset that significantly enhances the region’s touristic and sporting value. By promoting vertical mobility to high-altitude alpine zones that would otherwise remain logistically inaccessible, it promotes stratified tourism regime accommodating both high-performance athletes seeking technically demanding terrains and leisure-oriented visitors pursuing snow-based recreation. The winter sports sector, in turn, generates pronounced multiplier effects within local economies. Seasonal accommodations maintain operational continuity, thereby mitigating winter unemployment and stabilizing labour markets. A diverse set of livelihood actors, including sledge operators, ski and snowboard instructors, mountain guides, equipment rental entrepreneurs, transport providers, photographers, artisanal producers, and food vendors, are integrally dependent on the substantial seasonal tourist inflow. The size and variety of this engagement show that the sector is very important for changing the way income and wealth are distributed in a region, as well as for making the economy more diverse and resilient.

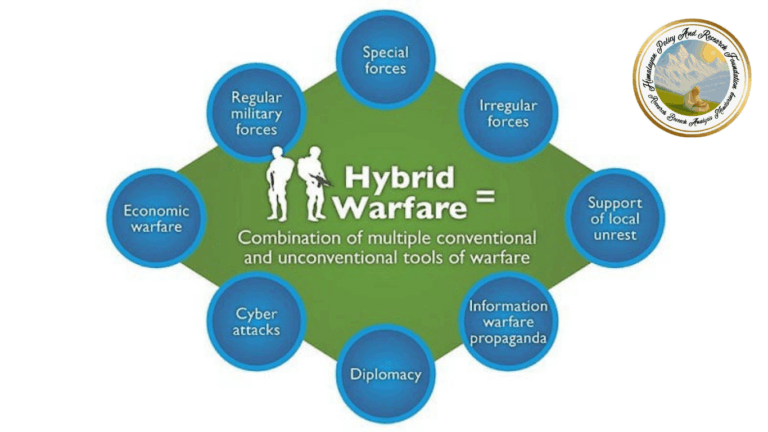

State-led interventions particularly through initiatives such as the Khelo India Winter Games, have further institutionalised this diversity. These sate interventions have made Gulmarg a more important part of India’s changing winter sports scene by bringing in more sports tourists, improving the physical and organisational infrastructure, and making winter sports a national development priority. Over time, additional resources have been put into maintaining slopes, monitoring avalanches, providing first aid and rescue services, and training facilities. This makes winter sports a more viable long-term business. Winter used to be a tough time for many families, especially those who lived in the countryside of Kashmir and Ladakh. Now, though, it is a time of opportunity and financial stability. The most important thing about winter sports in Jammu and Kashmir is how important they are to society and politics. The region, which has long been associated with conflict, violence, terrorism, security concerns, and political instability, has increasingly turned to sports as a medium of peace-building, youth engagement, and narrative transformation. Winter sports function as instruments of soft power, enabling the region to articulate an alternative narrative foregrounding aesthetic appeal, hospitality, adventure, and cultural vitality. Gulmarg and Ladakh convene national and international competitions that receive substantial media attention and illustrate quotidian vibrancy within contemporary spatial representations of the region’s socio-cultural structure as perceived globally today. Winter sports can be a good way for young people to let out their energy, drive, and creativity.

Young people are able to traverse outside of the area to compete in skiing, snowboarding, and ice hockey training programs. They can also play professional sports and meet athletes from all over the world. Aligning with Sport Development Theory, there is a progression from widespread participation to performance pathways that eventually lead to elite international representation. As local youth received training in snowboarding and skiing, the area entered the talent-identification stage and eventually produced elite athletes who represented India. In the early decades, winter sports in Kashmir were largely limited to tourism, foreign skiers frequenting Gulmarg in the 1960s and 1970s and adventure travellers navigating Himalayan slopes. Over time, institutions like IISM and the Youth Services and Sports Department established structured training frameworks, transforming recreation into organized sport.

Since its beginning in 2020, which had almost 1,000 athletes (306 of whom were women), the number of participants has steadily witnessed upward trend. In later editions, the total number of athletes grew to about 1,350 in 2021 and more than 1,500 in 2022. By 2025, there are expected to be more than 1,000 competitors in the Games in Gulmarg. These events include a growing number of snow-based sports, such as alpine skiing, Nordic skiing, ski mountaineering, snowboarding, and other new winter sports formats. This explores how the industry is becoming more diversified. Beyond its sporting significance, the winter-sports ecosystem possesses demonstrable potential for employment generation, tourism expansion, and regional economic stimulus.

This rise to elite performance is most clearly reflected in the international achievements of athletes from J&K. Gul Mustafa Dev became one of the earliest athletes from the J&K to represent India at the Winter Olympics in 1988. His participation marked a symbolic beginning, proof that a region shaped by mountains could shape world-class talent. Later on, Nadeem Iqbal from Rajouri represented India at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics as a cross-country skier, becoming the first J&K athlete to qualify for the Winter Games in that discipline. Arif Khan from Gulmarg marked a historic moment in 2022 when he qualified for the Winter Olympics in Beijing in both slalom and giant slalom becoming the first Indian athlete ever to earn direct quota spots for two Olympic ski events. His journey from local slopes to the world’s biggest winter-sport stage exemplifies the culmination of decades of regional development, social support, and environmental inspiration. The combination of natural landscapes, cultural heritage, economic benefits, and international achievements creates a multidimensional identity for winter sports in the region. They are not just about sports; they are also symbols of youth ambition and regional pride. Athletes from J&K taking part in events like the Winter Olympics, World Championships, and FIS races shows that the region is becoming more involved in the global winter sports scene.

Another important thing about this change in society and culture is that more women are choosing winter sports. Women and girls in both Kashmir are actively choosing skiing, snowboarding, and especially playing ice hockey which has become very popular in Ladakh. Their participation challenges traditional gender norms, broadens the scope of sporting culture, and symbolizes empowerment and progress. Women who trained teachers, coaches, and athletes from the area now represent Jammu and Kashmir at the national level and serve as role models for younger people. So, winter sports help bring about bigger social changes and make people feel like they belong in their community. However, the flourishing of winter sports in Jammu and Kashmir faces serious environmental challenges.

Climate change is a big threat to the ecosystems that depend on snow for survival, which is what these sports rely on. Rising temperatures across Himalayan region, unpredictable snowfall patterns, shorter winters, and glaciers melting are becoming serious ecological disaster. Snowfall that used to reliably cover Gulmarg, Sonamarg, and Pahalgam from December to March now witness irritant pattern which slows down the sports season and makes the slopes less consistent for skiing. The frozen lakes in Ladakh which are utilised for ice hockey, also had fluctuations in their freeze cycles, which made it hard to plan tournaments. These changes put winter sports at risk and require adaptive mechanisms like environmentally friendly tourism planning, controlled construction, waste management systems, awareness about conservation, and alternative livelihood strategies to help communities that rely on winter tourism. Without taking consideration sustainable development goals and durable practices, the economic and cultural essence of winter sports in the region could face irreversible disruption. The heart of winter sports here is the way they bring together natural beauty, human effort, economic opportunity, and cultural capital. Numerical data on winter sports looks at how the world and society change all the time. This shows how the land can affect people and how people can make economic prospects and be proud of the land.

In the end, winter sports in Jammu and Kashmir are more than just things to do on ice and snow. They tell a story about change: how topography can become exciting and challenging places, how communities can turn bad weather into good chances, and how a region can change its identity for the future. Winter sports will continue to be an important part of the region’s identity and economy as they change and improve with better infrastructure, more talented players, and more environmentally friendly practices. Their essence lies in the convergence of tradition and modernity, nature and culture, challenge and celebration, a convergence that defines Jammu and Kashmir’s unique relationship with winter and positions it as a premier winter-sport destination in the Himalayan world. Scholars and scientific community emphasize the imperative to safeguard the fragile Himalayan ecosystem from the adverse impacts of commercialisation, economic expansion, and athletic pursuits as winter sports diversify. Achieving equilibrium between economic opportunities and ecological accountability requires a coordinated, participatory governance framework grounded in environmental stewardship, long-term sustainability, and the meaningful engagement of all relevant stakeholders across the region’s diverse institutional landscape today.