Written by: Peerzada Muneer

In the mystic vision of Maulana Rumi, our outward identities, shaped by profession, education, culture, and the illusions of modernity, are merely fleeting costumes adorning the soul, concealing our deepest essence: pure consciousness, the unwavering guardian of Divine Light. Rumi urges that the soul’s greatest purpose is to journey home, to transcend superficial divisions and return to its primordial source. Yet, this calling is persistently neglected; humanity, in its daily life, prioritizes material pursuits, fleeting pleasures, and hollow achievements over spiritual awakening and self-recognition. The invitation to move from darkness to light, emphasized in Rumi’s teachings, is often ignored, even as each hardship and trial is meant to reveal our inner illumination.

Modern existence showcases a relentless departure from this spiritual path. Individuals increasingly embark on trajectories marked by greed, competition, and self-deception, not only inflicting harm upon others but also perpetuating unrecognized wounds within themselves. Across the globe, heinous crimes, wars fuelled by power, oppression of the vulnerable, trafficking of innocents, destruction of communities, and unchecked environmental exploitation, testify to a spiritual forgetfulness and a collective journey toward darkness. From the spread of ideological extremism to the normalization of corruption, exploitation, and deceit, the sacred mission of the soul is continually compromised. As society indulges in pride, jealousy, malice, and the pain of separation, it fails to heed Rumi’s wisdom: “If everything around seems dark, look again, you may be the light.”

The consequence of this ongoing neglect is manifest in the proliferation of new, subtler forms of harm. Among the gravest is the phenomenon of white-collar terrorism, systemic moral corruption enacted through the spheres of influence where power, privilege, and intellect converge. This affliction marks not only a tragic estrangement from the sacred core of human nature but also illustrates how far society has travelled from the light Rumi beckons us toward. White-collar terrorism, in its insidiousness, encapsulates a profound spiritual malaise: the deliberate compromise of truth, justice, and compassion for personal or institutional gain, deepening the chasm that divides us from our primordial essence and the Divine Light within.

Nowhere is this rupture more vividly embodied than in the chilling Red Fort attack of 10 November 2025, a blast whose operational sophistication and symbolic violence arose not from the shadows of deprivation, but from the citadels of learning and the privileges of the educated class.

Throughout the last several decades, the global conversation on terrorism has been rooted in the assumption that violence is seeded in marginality: that the rootless and resourceless, the unskilled and unlettered, turn to extremism as a desperate instrumentality against the indifference or injustice of the powerful. But the reality now emerging before us powerfully disrupts this narrative. White-collar terrorism, in which doctors, engineers, teachers, scientists, and professionals with impressive social standing leverage their specialist knowledge, institutional access, and social legitimacy to give terror a new, bone-chilling edge, demands a recalibration of our theories and our anxieties. The attack near the Red Fort in November 2025, executed with technical precision and logistical mastery, brought the world face to face with the fact that the boundary between learning and fanaticism, between knowledge and violence, has become dangerously porous. The Red Fort attack, with its imagery of destruction and the harvest of lives, thus stands as both literal and philosophical testimony that our present crisis is a crisis of consciousness, a crisis that strikes at the root of our collective being and at the heart of what it means to be human. (White Collar Terrorism)

Why do professionals, deeply schooled and economically privileged, turn to the path of violence? What has torn them away from the guardianship of the Divine Light? Psychological and social science research as well as lived historical experience suggest that the key to this riddle lies beyond the spheres of material deprivation. Contemporary analysis puts forth subjective grievances, identity dynamics, and meaning-seeking as the formative energies: humiliation, perceived moral injury, and professional or existential frustration can render even accomplished minds vulnerable to the rhetoric of righteous violence. Highly educated individuals may experience stunted aspirations, blocked access to recognition, alienation from community, or cynicism from chronic institutional incapacity. In such a condition, extremist narratives offer seduction: a transformation of grievance into cosmic duty, loss into sacred sacrifice, and weakness into power. It is here, in this psychic terrain of loss and longing, that the Faustian pact between intellect and violence is consummated. Ironically, the very processes of education and intellectualization may augment the capacity for constructing elaborate ethical justifications, or moral inversions, that transmute violence into a species of service or sanctity, and murder into martyrdom. Violence, in such moral calculus, is no longer criminality, but a sacred duty or a sanitizing fire. (White Collar Terrorism)

The Red Fort incident itself underscores this new logic of professionalised extremism. On that fateful November afternoon, Old Delhi was rocked by the calculated detonation of a white Hyundai i20, an act which instantly propelled not just local police but the National Investigation Agency to the center of public anxiety. The car itself, parked for hours in a location of historical and social resonance, became a symbol of cunning and patient malice; the aftermath, with its carnage and panic, gave way to the grim discipline of forensic investigation. Arrests soon followed, one of the first being Amir Rashid Ali, whose academic and community affiliations unfurled the thread of the larger operation. What shocked investigators and the public alike was not only the technical sophistication of the attack, but the discovery that the principal suspects were doctors, many affiliated with respected institutions and universities such as Al-Falah University. The counterterrorism playbook, traditionally populated by images of the deprived and disenfranchised, was suddenly and conspicuously obsolete. The script had changed. Educated, networked, professionally mobile individuals were not only conceiving and developing mass casualty plots but moving invisibly through trusted institutions, subverting the very architecture designed to guarantee security, health, and progress to society at large. The operational threat lay not just in their skill, but in their enormous camouflage, and in the chilling possibility that technical expertise can now serve violence with untraceable precision.

The implications extend far beyond the tactical or operational. Philosophically, this is a fragmentation of the social contract. The professions, medicine, engineering, pedagogy, are, in the public imagination, pillars of ethical rationality, service, and upward mobility. When their ranks are penetrated by radical networks, the betrayal is not simply of trust, but of meaning itself. The light that professionals are meant to carry into the world is dimmed, and the promise of progress is replaced with dread and suspicion. Moreover, the damage to institutional legitimacy and civil society is deep and slow to heal. As Rumi would see it, this is a forgetting of essence, a wandering from the root of consciousness.

Yet we must ask: Why does education, usually valorised as the surest defence against prejudice and fanaticism, fail in so many cases to inoculate against radicalisation? Part of the answer is structural: Education brings with it high expectations for economic security, social status, and political participation. In societies where institutions are strong and opportunity is expanding, these expectations breed stability and hope. But when institutional decay, unemployment, corruption, and blocked social mobility prevail, education becomes a double-edged sword. Ambitions rise but the means to fulfil them falter. The dissonance between what is promised and what is delivered creates a fertile ground for disillusionment, grievance, and the search for redemptive narratives. In search of dignity, meaning, and agency, some turn to radical alternatives, and the technical skills they carry serve not as barriers but as accelerants for the extremist project. (Krieger, More Education = Less Terrorism?)

The psychology of this transformation is complex. Research demonstrates that highly educated or intelligent individuals are no less vulnerable to psychological distress; in fact, their identities may be more fragile, their existential anxieties sharper, and their need for recognition more acute in environments that devalue or frustrate their aspirations. Extremist groups, well-aware of these vulnerabilities, shape narratives that exploit yearning for meaning, belonging, and significance. Recruitment is rarely an act of sudden brainwashing, but more often a gradual process of emotional grievance, peer validation, repeated exposure to sacred ideologies, and experiential isolation. Social exclusion, under-recognition, or humiliation, real or perceived, can tip even the rational mind towards violence when emotional or spiritual needs are unmet. Through the careful manipulation of group dynamics, repetition, and dependency, belief systems are reorganized, and sacred values are rendered non-negotiable.

Philosophical and psychoanalytic models provide useful frameworks for understanding the pathways of radicalisation. Identity theory explains that fragile, unstable, or excluded identities are easily harnessed by movements and groups offering immediate meaning, status, and belonging. Violence becomes a path to dignity and existential coherence, particularly when narratives of struggle and heroism are supplied. The narcissism-based model posits that unhealed wounds, often arising from early family environments or political subordination, allow humiliation to fester, generating displaced rage that extremist ideology weaponizes against symbolic enemies. Paranoia theory suggests that difficult internal conflicts or negative self-perceptions are projected outward, rationalizing violence as defense or preemptive strike. Absolutist and apocalyptic models, meanwhile, enable violence through rigidity, emotional numbing, and fantasies of purification, offering moral certainty for those who might otherwise be lost in ambiguity. (Victoroff, The Mind of the Terrorist)

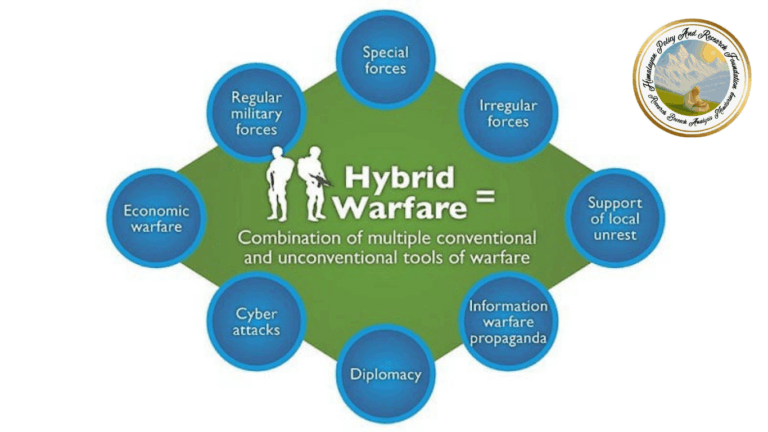

But there is also an institutional dynamic at play. Professional and academic networks impart legitimacy to radical claims that would otherwise be dismissed as fringe. Technical knowledge allows educated radicals to overestimate control and minimize risk, while the rationalizing impulse provides cover not just for personal shame but for the group dynamics of violence. Digital technologies, encrypted messaging, anonymized forums, algorithmic content recommendations, mean that radicalization is no longer dependent on geographic proximity. Professional cohorts are exposed, validated, and operationalized across virtual and physical domains. These new networks accelerate recruitment, operational security, and threat magnitude, placing intelligence agencies continually on the defensive, often unable to detect threats that lack criminal history, suspicious financing, or overt radical connections. (Youth Radicalisation ,White-Collar Terrorism)

The Red Fort incident is thus not a singular shock but a harbinger of what the new threat environment may look like. Education is no longer a firewall against violence; in some regimes, it becomes a ladder to more effective terror. Technical competence, social camouflage, access to sensitive resources, and the ability to move within the trusted spaces of civil society and the state all contribute to both operational lethality and public panic. The “fearless guardians” of modernity can, in moments of alienation or ideological capture, become bearers of destruction.

For policymakers and societies, the ethical and operational dilemmas are immense. Overreach, by criminalizing professions or universities or deploying blanket surveillance, may inadvertently build the very grievance and alienation that facilitates radicalisation, and may undermine the fragile trust that institutions depend upon. Under-reach, failure to adapt intelligence and prevention to the new reality, exposes society to unpredictable and devastating violence. Proportionality, evidence, and meticulous oversight are essential: intelligence operations must be grounded in clear suspicion and judicial review; interventions should respect civil liberties and avoid the collective stigmatization of professions or groups. Prevention cannot be reduced to policing but must involve community engagement, professional self-governance, mental health support, critical thinking, civic pedagogy, and the restoration of meaning and dignity to all citizens. (Why Terror Wears White Collar)

The literature and case studies also point toward the need for more comprehensive, multidisciplinary research, into elite recruitment, the interplay of professional identity with extremist narratives, and the efficacy of various mitigation strategies, from employee screening to digital counter-narratives. Comparative analyses with organized crime and insider threats highlight the unique hybridity of white-collar terrorism: secrecy and privilege are married not to profit, but to sacrifice and ideology, rendering many established policy frameworks inadequate. (Youth Radicalisation)

At the heart of the debate, every policy must wrestle with a final Rumi-esque truth: security, to be durable, must flow from consciousness, from a society rooted in dignity, justice, belonging, and spiritual integrity. The antidote to pan-extreme violence is not found solely in the arsenal of law or in the labyrinth of surveillance, but in the restoration of the soul’s anchorage. As communities confront the specter of radicalised professionals, they must also revive the traditions, disciplines, and practices that nurture wholeness, resilience, and the capacity to see the Divine Light in every citizen. (White Collar Terrorism)

White-collar terrorism, in all its forms, from the bombing at Red Fort to the more insidious erosions of trust and solidarity, reminds us of what is at stake. The struggle is not simply for life and property, but for the very possibility of meaning; not simply for the health of institutions, but for the courage and clarity of those who must bear witness to the future. The return “to the root of the root” is the return to consciousness, the unwavering assertion that technical skill or education, shorn of ethical and spiritual orientation, can become the accomplice of radical darkness just as easily as it can be the servant of light.

Having outlined the underlying meaning and broad causes of white-collar terrorism, it becomes essential to recognize religion as a primary motivator in societies where faith forms a central pillar of collective identity. In regions such as, but not exclusive to South Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa, religious affiliation shapes everyday existence and social boundaries, fuelling a strong sense of belonging but also a stark environment of religious “othering.” This process of situating one religion/religious identity in opposition to another has triggered a vast array of conflicts. From individual disputes to communal violence, and stretching to national and international tensions, the consequences of religious polarization are far-reaching.

This religious divisiveness is often intensified by politics, where the nexus of faith and political power amplifies sectarian loyalties and shifts the focus toward the mobilization of communities for specific agendas. Within this context, India’s turbulent history offers many examples of how religious fervour, when manipulated by political interests, produces tragic outcomes. The suicide bombings propagated by Jaish-e-Mohammad modules are emblematic; these acts of violence are orchestrated not only through dogmatic zeal but also underpinned by ideological and political aims, recruitment and justification occurring almost exclusively through a warped religious narrative.

What is especially disturbing is that perpetrators often include highly educated individuals, doctors, engineers, professors, who become enmeshed in such movements despite their worldly success and social privilege. The vale of Kashmir, in particular, illustrates this phenomenon: figures such as Dr. Manaan, Dr. Mohammad Rafi, and Dr. Umar represent a trend where advanced education and economic stability do not prevent radicalization or participation in extremist violence. The paradox remains that high intelligence and qualification rarely translate to nuanced or authentic understanding of religion; rather, such knowledge of faith is often either insufficient or deeply distorted. Within the labyrinth of religious sects, competing interpretations, and the proliferation of self-proclaimed scholars, misinformation spreads with alarming velocity, especially as radical ideologies are promoted, misrepresented, and accepted even by the learned.

This doctrinal confusion, magnified by crises, political ambitions, economic hardship, and amplified through technology and social media, lies at the heart of contemporary religious extremism. The problem is not merely a misinterpretation of religious texts but an active distortion of religious essence, transformed and weaponized by those seeking influence and control. The solution lies in building robust religious counter-narratives, led by responsible scholars and students who confront fanatic, rigid, and irreligious ideologies with wisdom, authenticity, and rational critique. Such a battle is fundamentally ideological and demands proactive, sincere engagement from states, through lectures, publications, curricula, and every possible instrument, to construct a resilient foundation of understanding, tolerance, and critical thought. This ideological confrontation must work in tandem with broader state measures across many fronts, forming a multi-dimensional defense against the growing threat of radicalization and white-collar terrorism.

The response, then, must be as holistic as the challenge. Only in a society that values Rumi’s inner journey, that cultivates vigilance and belonging together, upholds law and nurtures the soul, balances security with dignity, suspicion with trust, can pan-extreme violence be contained and ultimately transcended. The challenge of our age is to reclaim the educated not as technical functionaries, but as guardians of a light that must never be allowed to flicker. Only then will the circle of consciousness endure against the storm of violence, and only then, as Rumi exhorts, will we find the courage and grace to “return to the root of the root of your own soul.”