By: Irshad Ahmad ( Research scholar )

The political reconfiguration in Bangladesh in 2024, culminating in the ouster of Sheikh Hasina, constitutes one of the most analytically contested geopolitical events in contemporary South Asian political development. It has invited widespread debate among scholars and policy analysts over its causal dynamics, institutional implications, and the appropriate conceptual vocabulary through which to interpret the rupture. Scholars, policy observers, and political actors remain divided on the most appropriate conceptualization of the crisis. Central to the debate is whether the episode constitutes a coup—engineered or sanctioned by core state institutions—or whether it was the culmination of a prolonged, diffuse non-cooperation movement in which society gradually withdrew its consent, hollowing out the regime’s operational capacity before any elite intervention occurred.

The long-term political environment of Bangladesh provides the foundation for this debate. Over the past decade, the Awami League consolidated what Ali Riaz has defined as a competitive authoritarian system: an institutional arrangement in which electoral mechanisms exist but are increasingly subordinated to executive control. Political legitimacy is produced, reproduced, or perpetuated in such highly contested systems through a complex interaction of coercion, surveillance, patronage distribution, and developmental claims, in addition to competitive democratic competition. Riaz’s theoretical framework argues that controlling the line between social compliance and coercive power is crucial to the survival of competitive authoritarian regimes. The stability of the government is placed at risk when coercion becomes too stark or consent too brittle.

A significant but often underemphasized element of this long-term dynamic was the foreign policy recalibration undertaken by Sheikh Hasina in the months preceding the crisis—most notably her outreach to China in mid-2024. This diplomatic turn, culminating in new agreements, discussions on expanded investments, and a high-profile visit to Beijing, attracted considerable attention. While such engagement may be interpreted as driven by economic and infrastructural imperatives, segments of the Bangladeshi elite, as well as certain external observers, perceived the move as a potentially destabilizing geopolitical . For some domestic groups, it represented a departure from the traditional strategic balance that had defined Bangladesh’s foreign relations; for others, it signaled a possible re-alignment that “did not suit” entrenched interests and therefore became a politically consequential marker. By accelerating pre-existing tensions and altering the incentive structures facing coercive institutions, the China outreach serves as an illustration of how elite calculations can be altered by geopolitical signalling during times of domestic fragility.

The legitimacy threshold that held together the competitive authoritarian system had reached a breaking point.Support for the government’s developmental narrative declined , perceptions of widespread nepotism and corruption increased exponentially, and once-strong ruling-party networks were no longer able to mobilise as a single entity. These conditions were made worse by the emergence of a recognisable pattern of non-cooperation particularly among students, professional associations, and the bureaucratic sectors. The 2024 crisis was different from previous periods of unrest because of this new wave of civic disengagement. People started to distance themselves from the everyday cooperative behaviours that serve as the logistical underpinnings of state operations, rather than depending exclusively on street protests.Teachers declined to administer examinations; transport groups halted operations; university students boycotted ; bureaucrats quietly delayed or abandoned administrative tasks; and segments of the private sector scaled back cooperation with state directives.

These dispersed yet collectively potent actions correspond to K. Sabeel Rahman’s theoretical framework of “civic infrastructural cooperation”—the dense web of administrative routines and informal compliance norms that cannot be fully coerced from above. When citizens disengage from these infrastructural practices, the coercive capacity of the state becomes insufficient to sustain governance. The 2024 crisis evolved through precisely this erosion of infrastructural cooperation. While protests and demonstrations contributed to the political environment, the more consequential development was the widespread civic refusal to participate in the reproduction of state power. The regime’s administrative apparatus became increasingly paralyzed, not because it was directly attacked, but because it was indirectly abandoned. The state’s inability to extract cooperation from its own civil servants, educational institutions, and business groups revealed a profound crisis of governability. Even before elite institutions took visible positions, the government found itself unable to operationalize its authority across the country.

Against this backdrop, some scholars interpret the 2024 incident as a coup, contending that strategic elite withdrawal was the decisive factor in Sheikh Hasina’s fall. According to this argument, the final rupture occurred when the military and key bureaucratic sectors adopted neutrality or refused to implement government directives, even though civil unrest had set the stage. This perspective emphasizes the significance of what might be termed a “soft coup” or, more precisely, an elite intervention that shapes conditions to precipitate regime collapse without undertaking an overt, classical coup.

This interpretation finds resonance in Gary J. Bass’s observations on civil–military relations in South Asia. Bass notes that institutional recalibration is often triggered when legitimacy crises intensify, international reputational costs rise, or the loyalty of coercive elites threatens institutional interests. Moreover, this analysis coincides with Naunihal Singh’s concept of “coordination coups,” in which uncertainty regarding military loyalty resolves rapidly, generating swift political realignment. The speed and sequencing of events in Bangladesh in 2024 marked by abrupt military neutrality, rapid bureaucratic repositioning, and coordinated elite signaling—align with this framework more than with the slow, accumulative erosion characteristic of mass non-cooperation movements.

Applying Bass’s framework, political scientists argue that the Bangladesh military leadership shifted its stance when public opposition reached critical mass, enabling them to justify neutrality as responsiveness rather than ambition. The synchronised coordination between high-ranking bureaucrats, technocrats, and security elites reveal a coup-like trajectory. The military’s sudden neutrality neither defending nor forcibly removing the government constitutes a strategic equilibrium designed to avoid direct attribution of responsibility while enabling political transformation.

However, the challenge is in distinguishing causality from correlation . While elite defection undeniably shaped the immediate outcome, it remains analytically incomplete to interpret the 2024 episode solely as a coup without examining whether institutional elites acted because they intended to remove the government or because they recognized that the government could no longer be defended in this situation. This distinction is crucial. A coup requires elite initiation. A non-cooperation movement produces elite adaptation. By the time military and bureaucratic actors shifted their stance, the state’s capacity to enforce decisions had already eroded sharply. Administrative paralysis was widespread; the police had lost operational control in many districts; ruling-party networks were unable to mobilize counter-protests; and state-media narratives were met with unprecedented disbelief.

Elite action thus responded to, rather than caused, the collapse. This dynamic fits into a larger theoretical tradition that sees authoritarian breakdowns as complex processes that exceed the binary of “coup” versus “non-cooperation movement.” Political sociologists have long observed that authoritarian regimes typically fall by way of cumulative disengagement rather than outright overthrow. Elites only conclude that repositioning is necessary when institutional governability declines, cooperation collapses, and consent erodes.

The second crucial area of attention is the political composition of the post-Hasina interim political arrangement. Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel laureate and internationally recognised economist, was appointed interim leader after her departure.His appointment was sanctioned through constitutionally empowered processes during an extraordinary political moment, providing immediate symbolic legitimacy, technical expertise, and international recognition. Yet this sort of leadership poses significant questions about democratic legitimacy: Yunus did not accede to power through popular mandate but through an emergency procedural process. His authority is therefore legitimacy-ambiguous in classical democratic terms, creating a complex relationship between procedural legitimacy through appointment) and performance legitimacy earned through governance. Comparative scholarship on technocratic interim governments stresses that such legitimacy ambiguity shapes how domestic factions interpret transitional authority and how external actors calibrate their engagement.

A third important indicator is the visible link between the Yunus-led interim administration and prominent transnational philanthropic networks such as the Open Society Foundations (OSF).The conversations between Yunus and Alex Soros and OSF’s declarations of support for Bangladesh’s transitional phase are instances of empirical indicators or data of transnational engagement. These indicators demonstrate the increasing involvement of international philanthropic actors in governance transitions by offering advisory assistance, reputational capital, and normative support, rather than implying causative influence.In the Bangladesh context, the visibility of such engagement became a subject of domestic debate, particularly among groups attentive to questions of sovereignty, external influence, and the role of international civil society. Such linkages therefore constitute an analytically relevant dimension of the 2024 breakdown, without implying prescriptive judgment.

A fourth geopolitical indicator pertains to India’s posture.Although India is Bangladesh’s closest neighbour and a key strategic ally in its immediate neighbourhood, it managed to stay out of the country’s internal political reorganisation. Delhi adopted a two-pronged strategy ,offering Sheikh Hasina humanitarian protection while adamantly refusing to get involved in Bangladesh’s political turmoil.This maneuver allowed India to uphold regional norms of sovereignty, avoid charges of interference, maintain diplomatic flexibility, and signal continued personal and political solidarity with a long-standing partner. India’s adjusted approach also ensured that the crisis did not escalate into a regional flashpoint and that New Delhi’s long-term relationships were neither weaponized nor abandoned.

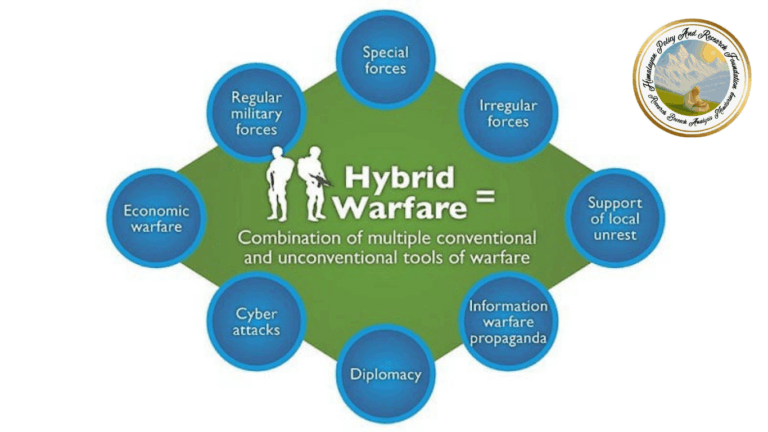

In the meantime, Islamist organisations in Bangladesh, both parliamentary and extra-parliamentary, smartly mobilised supporters by taking advantage of the regime’s legitimacy crisis. These actors used religiously coded narratives to undermine the legitimacy of the regime while operating within neo-fundamentalist frameworks. However, because of their limited ability to coerce, they were unable to independently bring about regime change and they acted as ideational stimulants,intensifying the normative contestation surrounding the state. In addition, by influencing elite expectations through strategic encouragement, geopolitical leverage and covert signalling, external actors including regional powers like China and Turkey contributed indirectly to the crisis environment in Bangladesh’s political reordering. These factors are consistent with Powell’s (2012) theory of internationalised coups, which holds that foreign involvement alters the incentives of domestic elites without directly coordinating mass mobilisation.

The Bangladesh 2024 episode can therefore be understood as a coup embedded within a permissive socio-political environment marked by relative deprivation, Islamist mobilization, transnational normative signaling, and geopolitical recalibration. Relative deprivation created legitimacy erosion; Islamist actors supplied moral pressure; foreign actors subtly modified elite incentives; and domestic discontent created atmospheric density.

Yet the nearby causal mechanism remained elite coordination and defection is consistent with theories of authoritarian power-sharing failure (Svolik, 2012) and praetorian intervention (Huntington, 1968).

These events demonstrate that while popular grievances and discursive mobilization were politically visible, they did not constitute the causal engine of regime collapse. Instead, the regime was displaced through elite action with widespread unrest acting largely as a veneer of legitimacy and symbolism. Bangladesh 2024 therefore represents a paradigmatic case in which a formally civilian,quasi-democratic regime was ousted without the procedural or institutional characteristics of a democratic transition. It vindicate the enduring primacy of coercive institutions, elite coordination, and strategic calculations in authoritarian resilience and breakdown.Thus, analytically, Bangladesh 2024 must be classified as a coup layered upon relative deprivation, infrastructural non-cooperation, geopolitical entanglement, and transnational signaling, rather than as a non-cooperation movement or democratic transition. Any alternative framing misreads the causal hierarchy and obscures the centrality of coercive institutions in determining authoritarian regime breakdown.

The fall of Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League government is therefore best understood as a paradoxical case wherein a quasi-democratic regime was removed through elite force without democratic institutional transition—demonstrating once again that authoritarian endurance and collapse remain grounded in the strategic decisions of elites navigating a changing domestic and geopolitical landscape.

References:

Bass, G. J. (2015). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Vintage.

Huntington, S. P. (1968). Political Order in Changing Societies. Yale University Press.

O’Donnell, G., & Schmitter, P. C. (1986). Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Powell, J. (2012). Determinants of the attempt and outcome of coups d’état. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(6), 1017–1040.

Rahman, K. S. (2017). Democracy Against Domination. Oxford University Press.

Riaz, A. (2019). More Than Meets the Eye: The Bangladeshi State, Society, and Elections. Routledge.

Sharp, G. (1973). The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Porter Sargent Publishers.

Singh, N. (2014). Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Svolik, M. W. (2012). The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, C. (2006). Regimes and Repertoires. University of Chicago Press.