By: Dr Zahid ( Freelance Researcher)

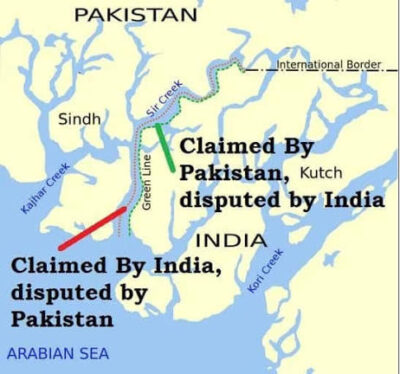

There are border disputes that define the psychology of a state more than its cartography. Sir Creek, the colonial brand-name of Ban Ganga, is a narrow, shifting tidal estuary of barely ninety-six kilometres in the Rann of Kutch. Though seemingly peripheral on the map, it animates the deeper philosophical question that shapes the Indian state’s notions of law, justice, and rationality: whether boundary-making must rest upon the cold force of colonial precedent or the moral and legal rationality of international law. It is not merely about where a line should be drawn between Gujarat and Sindh, or how much of the Arabian Sea’s continental shelf each side may claim. It is also about whether we continue to be governed by the bureaucratic residues of an empire, the 1914 Bombay Resolution Map (B-44), which placed the boundary on the eastern bank for revenue-administrative convenience, and which Pakistan has elevated into a sacrosanct legal instrument fixing sovereignty on that bank. Yet, the language of the 1914 agreement is administrative, not sovereign, it defined jurisdiction for revenue and policing, not the permanent line between two international entities that did not yet exist. To turn such an administrative convenience into a final boundary is to mistake the residue of empire for the law of nations (Menon, 2002). In this sense, the Sir Creek dispute is a living tension between inherited cartographic fixation and the ethics of lawful precision in a post-colonial world.

Yet beyond lawfare and textual cartography, Ban Ganga is also an ecologically sensitive mudflat-estuarine cradle that hosts flamingos and other migratory birds, and is Asia’s largest fishing ground sustaining thousands of fisher households. Beneath its shifting channels lie potential oil and gas reserves whose exploitation carries strategic consequences for maritime energy security, surveillance corridors, and naval preparedness in the Arabian Sea. Thus, the western “boon” of Ban Ganga becomes simultaneously a legal archive, a colonial mis-inscription, a living ecological nursery, and a strategic frontier. Its future therefore requires a patient, forward-looking craft, one that integrates ecological stewardship, sustenance-economy livelihoods and responsible maritime strategy, and not merely a narrow obsession with a line drawn by a colonial bureaucracy more than a century ago.

India’s position, by contrast, is neither an act of aggression nor expansionism; it is an insistence that international law, when applied consistently, must govern how rivers, estuaries, and creeks are demarcated. India maintains that Sir Creek is a navigable channel and that according to the thalweg principle, the boundary must lie along the mid-channel or deepest line of the navigable stream. The thalweg principle, established in nineteenth-century European river jurisprudence and affirmed by international law in the twentieth century, posits that in navigable rivers forming a boundary, the line of deepest channel represents the fairest and most functional division (Beckett, 1967). This is not an arbitrary rule: it emerges from the logic that navigable rivers are arteries of communication and trade, and thus cannot be monopolized by one side. The mid-channel ensures equitable access and equal sovereignty.

The thalweg principle has long been the grammar of civilized coexistence along waterways. From the Rhine between Germany and France to the Danube across Eastern Europe, the doctrine reflects not only the law’s geometry but its moral reasonableness. To India, the thalweg represents an equitable, contemporary, and internationally validated approach to boundary demarcation – in contrast to Pakistan’s dependence on colonial cartography that disregards both hydrological change and the modern law of the sea (UNCLOS, 1982). If Sir Creek is indeed navigable, then under international law, its boundary must follow the thalweg.

The question, of course, is whether Sir Creek is navigable. Pakistan insists that it is a shallow tidal channel, incapable of supporting navigation and therefore exempt from the thalweg principle. India’s hydrographic surveys, dating back to the colonial era and reaffirmed by post-Independence studies, show otherwise. The Survey of India (1968) and subsequent joint hydrographic investigations confirm that while the upper reaches of the creek are shallow, the mouth remains subject to tidal ingress from the Arabian Sea, allowing limited navigation (Ministry of External Affairs, 2007). Navigation in international law does not imply commercial shipping alone; even small craft movement, tidal connectivity, and the ability of waterborne passage suffice to classify a watercourse as navigable (Oppenheim, 1955). Thus, the navigability of Sir Creek, especially near its mouth, activates the thalweg principle.

There is also the matter of precedent. When states succeed colonial administrations, they inherit borders under the doctrine of uti possidetis juris – that is, colonial administrative boundaries are presumed to become international boundaries. But uti possidetis is not absolute; it yields where there exists a clear rule of international law or treaty interpretation to the contrary. The International Court of Justice (ICJ), in the Burkina Faso v. Mali case (1986), held that while uti possidetis ensures stability, it must not fossilize injustice or contradict the principles of equity and effectiveness. India’s invocation of the thalweg principle does not disrupt inherited stability; it refines it through law. It ensures that the boundary between India and Pakistan evolves from colonial convenience to international legality.

To argue that the eastern bank is final simply because a colonial map once said so is to accept that law must serve the dead hand of empire rather than the living requirements of justice. Boundaries must respond to nature as much as to history. Sir Creek’s hydrology – tidal, shifting, and alive – defies static interpretation. It is not a man-made canal but a living estuary whose navigable capacity changes with the rhythm of the sea. The 1914 map, drawn before the refinement of international law on fluvial boundaries, cannot anticipate the complexities of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which lays down that delimitation of territorial seas and exclusive economic zones must be based on “equitable principles, taking account of relevant circumstances” (UNCLOS, Art. 15). India’s position flows from this modern understanding of law as a living equilibrium between geography and justice.

Pakistan’s reading, by contrast, appears to freeze time. Its insistence that Sir Creek is wholly non-navigable and that the 1914 resolution is binding reveals a broader pathology in subcontinental diplomacy: the nostalgia for fixedness. The subcontinent, traumatised by Partition, has cultivated an anxiety for immovable lines. In this anxiety, even a creek that shifts with the tides is forced into the rigidity of political dogma. Yet this rigidity undermines not only law but the very idea of pragmatic coexistence. If every map must remain as the colonial official drew it, diplomacy is reduced to the archaeology of resentment.

Sir Creek is also a mirror of India’s evolving self-image. India’s argument for the thalweg is not just legal but civilizational. It reflects the conviction that the postcolonial state must reconcile sovereignty with reason, and strength with fairness. The Indian state, by grounding its position in international maritime law rather than emotional nationalism, demonstrates that legality is not a concession but a form of power. Law, when rightly applied, is the highest form of strategic restraint. It is this moral confidence – that India can trust the principles of law to vindicate its interests – which distinguishes it from the reactionary nationalism of its neighbours. The thalweg principle is thus both a legal instrument and a philosophical statement: that boundaries, like reason, must follow the deepest channel.

The Pakistani argument, though couched in legality, is ultimately trapped within the scaffolding of political insecurity. It holds that Sir Creek is not navigable and therefore the thalweg principle is inapplicable. It also claims that the 1914 Resolution is final, and that India’s insistence on revisiting the issue represents a unilateral attempt to redraw settled boundaries. This argument ignores both hydrological reality and the evolution of international legal standards. The notion of navigability is not a static concept- it must be judged contextually, relative to local conditions, tidal influence, and the functional capacity of the channel. In international law, navigability extends beyond the mere passage of ships; it encompasses the potential of a watercourse to sustain transport, fisheries, or communication during any part of the year (Shaw, 2008). Sir Creek, being a tidal estuary that opens into the Arabian Sea, meets this criterion, at least in its lower reaches. The denial of navigability is, therefore, an act of political convenience rather than legal precision.

Pakistan’s claim that the 1914 Resolution was a definitive treaty is equally fragile. Even a cursory reading of the document suggests that its intent was administrative, not sovereign. It referred to police and revenue limits, not maritime entitlements. In contrast, when states become independent, their international borders are defined by instruments that clearly denote sovereignty. The 1914 agreement lacks this quality. The British, characteristically, left the demarcation of the Creek vague, perhaps knowing that estuaries are mercurial entities. To transform this bureaucratic vagueness into a binding international frontier is to commit what legal scholars call the “error of perpetuated ambiguity” (Brownlie, 1998).

More importantly, the consequences of accepting Pakistan’s interpretation are grave. If the entire Creek is deemed Pakistani, India would lose not merely a sliver of marshland but a decisive influence over the adjoining maritime zones. The boundary at Sir Creek serves as the base point from which the maritime boundary in the Arabian Sea is projected. A shift of even a few hundred metres at the Creek translates into a displacement of several thousand square kilometres of potential Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The stakes are not symbolic; they are economic, strategic, and environmental. Control over maritime zones influences access to hydrocarbons, fisheries, and undersea resources, as well as the range of naval operations and coastal surveillance (Ministry of Defence, 2013). Thus, India’s insistence on the thalweg is not about cartographic pride- it is about ensuring that international boundaries correspond to both natural equity and strategic necessity.

Pakistan, however, has sought to politicize what is essentially a hydro-legal issue. By framing India’s position as revisionist, it seeks to draw moral equivalence between a legal argument and a political provocation. This mirrors a broader pattern in South Asian diplomacy where reasoned legalism is often interpreted as aggression. Yet the thalweg principle is neither novel nor unilateral. It has been upheld in multiple international adjudications. In the Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso v. Mali), the International Court of Justice (1986) affirmed that natural boundaries like rivers must be interpreted in light of equity and functionality. Similarly, in the Kasikili/Sedudu Island case between Botswana and Namibia (1999), the Court reaffirmed that when a river serves as a boundary, the thalweg- the line of deepest navigation- represents the fairest delimitation. India’s reliance on the thalweg is, therefore, not a deviation from international norms but their affirmation.

This is what makes the dispute emblematic of the moral asymmetry in India-Pakistan relations. India argues from law; Pakistan argues from sentiment. India’s argument is structured around the continuity of international jurisprudence; Pakistan’s is structured around the discontinuity of historical trauma. Sir Creek, like Kashmir in another dimension, becomes a theatre where Pakistan’s political psychology manifests its need to preserve grievance as identity. The rigidity of its claim is less about territory and more about the fear of concession. Yet diplomacy demands that nations not be prisoners of their own rhetoric. A state that interprets every negotiation as betrayal cannot mature into a partner of peace.

From an Indian standpoint, the moral high ground lies in the ability to transform disputes into opportunities for legal and institutional innovation. India’s approach to Sir Creek demonstrates precisely that. It has repeatedly offered joint surveys, technical committees, and even third-party hydrographic verification. The 2007 joint survey was a milestone in this direction, confirming that the Creek is tidally influenced and partially navigable. Yet Pakistan hesitated to translate technical consensus into political agreement. This hesitation is rooted not in legal doubt but in domestic vulnerability. Any settlement that appears to concede even a metre of land, however rationally justified, is seen by Pakistan’s internal establishment as political weakness. The discourse of nationalism there feeds on intransigence. India, by contrast, can afford to be flexible precisely because it is confident in its legal footing.

At a deeper level, the Sir Creek dispute is a reflection of two contrasting ideas of the state. India’s statehood has been historically tied to the notion of law as a moral restraint. The constitutional imagination of India presupposes that sovereignty must operate through reason, not passion. Its foreign policy, though occasionally muscular, is fundamentally guided by the logic of rules. Pakistan’s statehood, in contrast, emerged through the negation of the “other.” Its nationalism was reactive, born of the need to define itself in opposition to India. Consequently, its engagement with disputes like Sir Creek is framed less by international law and more by the fear of appearing subordinate. This psychological difference manifests in the legal discourse itself: India invokes the universality of the thalweg principle; Pakistan insists on the sanctity of a colonial-era map. One looks to the future of law, the other clings to the debris of empire.

Yet, it would be too easy to caricature Pakistan’s position as merely obstinate. The deeper tragedy of South Asian geopolitics is that mistrust has colonized reason. Each technical argument is read through the prism of security paranoia. When the thalweg principle is proposed, it is not judged by its logic but by who articulates it. The consequence is paralysis: both states remain trapped in symbolic disputes even as global maritime law evolves around them. The cost is borne not by governments but by people – especially fishermen who, unaware of invisible maritime boundaries, are arrested for crossing into what each side claims as its own waters (Kumar, 2014). The Sir Creek dispute thus encapsulates how the absence of legal clarity translates into the suffering of ordinary lives.

For India, therefore, the resolution of Sir Creek is not merely a question of territorial assertion but of moral coherence. A state that aspires to global leadership cannot afford to have open-ended legal ambiguities on its periphery. The Indian argument for the thalweg is not an act of defiance; it is an act of faith – faith in the capacity of law to resolve what history has confused. This faith, however, must be accompanied by strategic patience. India must demonstrate that legality and restraint are not weakness but strength; that justice, when grounded in law, is more enduring than the transient victories of cartography.