Written by: Peerzada Muneer

When the fog of early autumn 1947 began to gather over the snow-clad valleys and forested ridges of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir, no one could have foreseen the grim chapter about to unfold. Beneath the façade of calm, the region’s centuries-old equilibrium, of Dogra rule over a majority-Muslim populace, of mountain passes and glacial lakes traversed by shepherds and pilgrims, and of a tradition of local syncretism and shared culture, was trembling. And when the first waves of tribal invaders swept down in October, the state quite literally stood alone: its ruler unsure, its forces stretched thin, its people bracing for a storm.

The socio-political milieu of the time was fraught. Jammu & Kashmir was one of the largest princely states in British India, ruled by the Hindu Dogra monarch Maharaja Hari Singh despite a clear Muslim majority in many districts. The British Raj’s departure in August 1947 left the princely states with the options of joining either the newly-created nations of India or Pakistan, or even trying to remain independent. In Kashmir’s case, Hari Singh initially sought to remain independent, neither acceding to India nor to Pakistan, hoping to preserve his state’s autonomy. Scholars note that the political landscape was already complex: the All Jammu & Kashmir Muslim Conference leaned towards Pakistan, while the Jammu & Kashmir National Conference, led by Sheikh Abdullah and powerful in the Kashmir Valley, inclined toward India and secular politics.

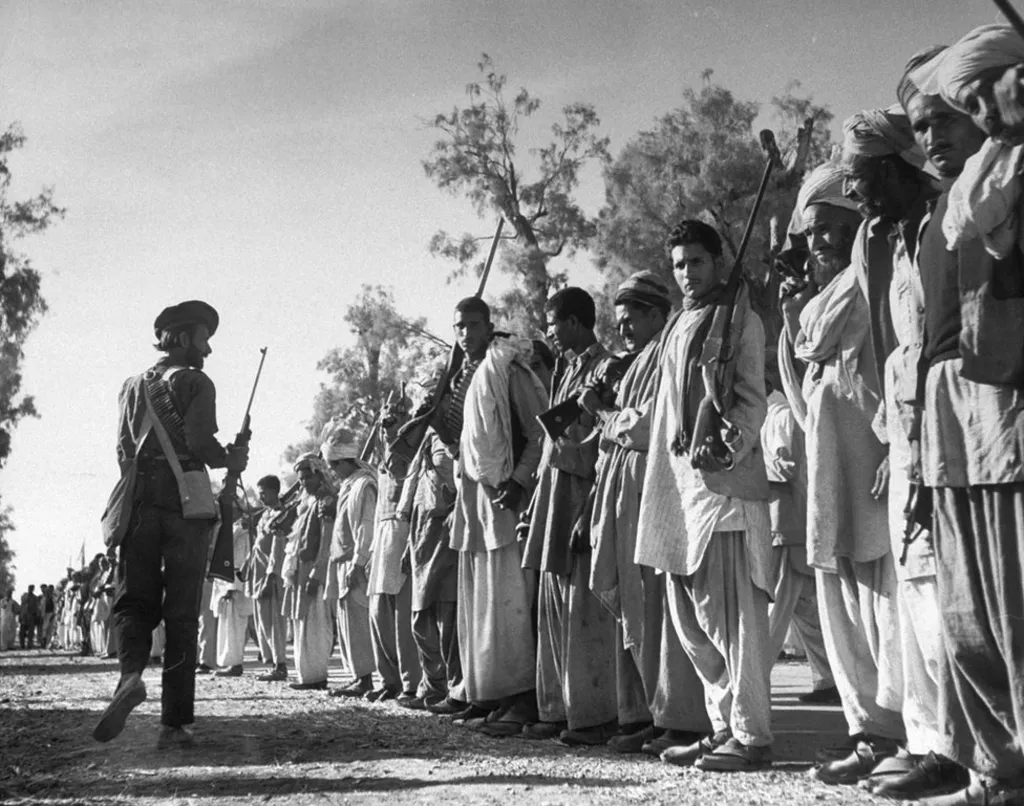

Against this backdrop, the partition’s communal ruptures and the emerging struggles over state identity played out in microcosm in Kashmir. The Poonch jagir rebellion, tax grievances, ex-servicemen’s unrest, and communal undercurrents all contributed to an atmosphere of simmering tension. Meanwhile, Pakistan viewed Kashmir, Muslim-majority, geographically contiguous (from its perspective), and strategically located, as a natural object of accession, and began covert preparations. On 22 October 1947, the fateful brush-fire ignited: tribesmen from the Pashtun-areas, supported and armed in large part by Pakistani military-backing, poured across into the state under an operation codenamed Operation Gulmarg.

The invasion was sudden, ruthless and dramatic. At dawn, tribal lashkars, recruited in the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), many thousands strong, moved through mountain passes, descending into Muzaffarabad, Domel, Uri and ultimately the approaches to Srinagar. They were aided by deserters from the State Forces. The invasion is described by many as “the darkest day in the history of J&K.” The Maharaja, recognizing the existential danger, sent a plea for Indian assistance, but Indian troops could legally come only after accession to India. On 26 October, Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession, and immediately the Indian Army began airlifting troops into Srinagar.

Yet, in those darkest hours, the weaving of history is rarely just about armies and treaties. It is about the ordinary people who, in extraordinary moments, chose to stand. As the state’s official forces wavered or were overwhelmed, a host of civilians and local volunteers rose up, across religious, ethnic, and regional divides, all united by a simple self-sacrifice: the resolve to defend their home, their neighbours, their humanity. Their names are often unsung. Their deeds seldom headline histories. But their contributions were vital.

Here, we honour a large number of such unsung heroes of that 1947 invasion, each acted in a moment of peril, each laid aside difference, each gave more than they could yield, and each deserves remembrance. The argument is firm: no sacrifice is lesser than another. Their lives, whatever their region, religion or official status, count equally in preserving what Kashmir stood for.

Take, for example, the elderly woman of Sopore, Zoon Ded, in the chaos when raiders burst into Baramulla and surrounding villages, she sheltered wounded civilians of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh faith alike, fed them, and helped them escape through forest tracks. Her household became a refuge when so many homes were turned to targets. Her legacy as “Zoon Ded Maej” (“mother”) in local oral history quietly reminds us that not all heroes carried rifles; some carried compassion.

In Handwara, the young volunteer Mir Maqbool Bhat and his village scouts guided Indian troops through unfamiliar terrain, acting as the eyes and ears of defence when official forces faltered. He was killed in an ambush while carrying ammunition for soldiers. His name echoes in folk-songs as “Maqbool-e-Handwara.” His sacrifice underscores how local courage supported the larger war effort.

Similarly, the teacher in Baramulla, Girdhari Lal, called the “Masterji who refused to flee”, organised neighbourhood youth into volunteer defence groups, gathering hunting rifles, signalling alarms, and warning nearby posts of enemy approach. His was not the formal title of soldier, yet his civic leadership helped his town survive.

In Budgam, the village elder Sheikh Ghulam Rasool rallied men to defend a shrine and mosque from desecration, thereby preserving communal dignity and inspiring surrounding hamlets to resist. Religious buildings in those moments became symbols of the social fabric worth defending.

In Srinagar’s urban quarters of Rainawari and Habba Kadal, groups of Kashmiri women, unnamed in many official records, stayed behind when many fled, tended to the wounded of all faiths, distributed food, and protected children. Many hid non-Muslim neighbours from raiders, refused to abandon homes, became silent saviours in a storm of fear. Their quiet courage forms the unseen feminine chapter of that 1947 story of survival.

Turning to the official state forces, the Muslim non-commissioned officer Habib Ullah Khan, from Ganderbal, refused to desert when tribal invasion began, led a counter-attack near Uri, and was shot saving his platoon commander’s life. His loyalty defied the propaganda of mass defections and proved that duty transcended communal stereotypes.

In Budgam again, the community leader Mian Bashir Ahmed (associate of Sheikh Abdullah) mobilised local men to protect both Hindu and Muslim villages from raiders, a civic resistance rooted in unity, not division. The trader Khawaja Abdul Rahim of Baramulla was beaten to death for refusing to betray hiding Sikh and Hindu neighbours. He “chose humanity over fear” at the cost of his life. Religion did not determine his action, compassion did.

The imam Maulvi Ghulam Hassan of Sopore, when raiders sought to inflame communal passions, addressed his Friday congregation urging Muslims not to aid the invaders, calling them “enemies of Islam and humanity.” In doing so he invoked the moral dimension of faith, not communalism.

Civilian organiser Tika Lal Sapru in Srinagar formed a voluntary civilian guard unit in October 1947 to maintain calm and assist rescue operations; his group protected government stores and bridges until Indian troops arrived. In Rajouri, Chowdhary Noor Din fought with Indian forces to retake the fort from raiders in 1948, an example of Dogra–Muslim cooperation in defending the state.

From Kupwara came Ghulam Mohammad Mir who helped Indian troops navigate mountain passes toward Tithwal and Kupwara, saving them from ambush. Students of Sri Pratap College in Srinagar volunteered as messengers and supply carriers; some later joined the J&K Militia (now JAK Rifles). Their youthful patriotism marked the civilian-military link in modern Kashmir’s defence.

At the formal military level, the Muslim officer Major Khusro Hussain Khan from Poonch stood firm with Brigadier Rajinder Singh, dying defending the Uri road, his loyalty demonstrating that soldiering in Kashmir was plural. The shepherd-spy Ghulam Mohi‑ud‑Din of Trehgam used his mountain-path knowledge to track raiders and inform Indian units; his rugged service underscores how geography and local knowledge mattered. The boatman Ali Mohammad Lone of Bandipora ferried refugees and soldiers across Wular Lake under heavy firing, a simple craft made heroic through risk and service.

In Baramulla hospital stayed Dr. Naseeruddin, treating the wounded of all faiths; he was captured and executed by raiders. His death is a martyrdom of humanity. In Srinagar, the civil-defence volunteer Pandit Triloki Nath Raina led night-watch groups guarding bridges and supply depots, preventing sabotage of the Amira Kadal bridge. The merchant Khawaja Noor Shah of Baramulla spoke out against loot and desecration; he was killed on the spot. His torn cap is still preserved by descendants as relic of defiance.

In Kulgam, teacher-volunteer Mir Akbar Ali formed a village defence group of students and farmers; his is a story of South Kashmir’s civilian resilience. Veteran Subedar Major Thoru Ram of J&K Infantry (a World War II veteran) led forces around Uri who refused to retreat after Boniyar fell, delaying the enemy approach to Baramulla. His stand buys time, enabling evacuations and reinforcements. In Baramulla again, the postman Abdul Ahad Khan guided families to safety through forest tracks when raiders entered, his tool was a mail bag, his mission human rescue.

In Poonch, Thakur Fateh Singh organised armed resistance in the hills even before Indian Army arrived; local men knew their terrain, and under his leadership they were the “people’s war” in that region. In Uri, Mir Ghulam Qadir saved stranded Sikh pilgrims by hiding them in his home until reinforcements came, a bridge of faith in a time of fear. In J&K Infantry, the signalman Naik Ganga Ram destroyed communication sets so that raiders would not capture them, falling in battle near Uri, technical service turned sacrificial.

And women too: Haneefa Begum founded the Women’s Self-Defence Corps in Srinagar, trained women in weapon-handling, first aid and discipline; Khatija Begum led militia training sessions in Fateh Kadal and Budgam; Jana Begum of Kulgam mobilised rural women to protect supply lines and assist wounded soldiers; Asha Devi (student volunteer) evacuated children and elderly; Shanta Koul (volunteer nurse) organised first-aid camps; Shyama Raina (Srinagar volunteer) stayed to guard neighbourhood temples and helped Muslim neighbours guard mosques too; and the Italian nun Sister Teresalina at the Baramulla Mission Hospital refused to leave the wounded when raiders stormed, she died protecting patients. These acts of courage, of women stepping into traditionally unheralded roles, underscore that defence of the homeland was not just a male domain.

In the villages: Rahmat Bibi of Kupwara (the “Mountain Mother”) gave food, shelter, and directions to Indian troops; her home became a rest-stop called “Rahmat Kuth.” Sati Devi of Rainawari set up food-kitchens in temples and schools for displaced families; Wazira Begum of Baramulla survived massacre and later testified to humanitarian teams documenting atrocities, one of the earliest female survivors to speak truth to history; and Dr. Naseem Jahan, one of the first Kashmiri Muslim women doctors, remained under curfew treating civilians and soldiers alike.

These many actors, teacher, trader, scholar, boatman, soldier, nurse, imam, student, woman volunteer, combine to form a mosaic of resistance. Their stories may differ in scale, context, or role, but their essence is the same: self-sacrifice, solidarity, service. They stood when the state stood alone.

Why emphasise their contributions? Because in the grand narrative of wars, treaties, generals, armies, maps, lines of control, the civilian story often fades. Yet the defence of Kashmir in 1947 was as much about ordinary Kashmiris defending homes, villages, and values, as it was about troops and guns. And in a region so easily compartmentalised along communal, regional, or sectarian lines, the fact that so many acted across such divisions is itself a testament to what Kashmir once aspired to be: a land where humanity mattered more than identity alone.

But let us be clear: to honour some is not to rank others. One cannot belittle one sacrifice over another, because sacrifice is not a contest. Whether the schoolteacher who organised alert lamps died alongside a rifle-bearing soldier, or the boatman who ferried refugees in a skiff while under fire, or the woman who held the hands of wounded men and women of all faiths, each reached for more than comfort, each risked life, each gave beyond self-interest. The fabric of Kashmir’s 1947 defence is rich only because every thread counts.

The broader historical implications are stark. The invasion of October 22-23 1947 set the tone of the conflict. The tribesmen’s advance, captured in sources, reached within striking distance of Srinagar and compelled accession to India and full-scale war. Once Indian troops arrived, they fought alongside local militia, state forces and civilians. The war of 1947-48 ended in a cease-fire of January 1949 and left the former princely state divided; the “Line of Control” emerged. But the human story of what happened in those first days of invasion, when the Maharaja’s forces were on the back foot and villagers held bridges, hidden paths, and hospital wards, remains the enduring one.

It is in this context that the heroism of these unsung individuals is of profound significance. They shielded the vulnerable when institutional support was weak. They crossed religious or caste divides when chaos threatened to tear the social fabric. They operated not for awards or recognition, but because it was right, because their people called for it, because their conscience would not let them run. The legacy of their courage deserves preservation not only in local oral memory but in the national and regional historical consciousness.

As years turned into decades, and the Kashmir conflict moved through insurgencies, cease-fires, political reforms, and international mediation, it risks becoming an abstraction: lines on the map, geopolitical manoeuvres, state narratives of victims and heroes. But when we remember those who stood alone and said “no” to fear, villagers, women, teachers, boatmen, nurses, we humanise the story. We reclaim the dignity of ordinary Kashmiris who paid the price of their decisions.

And what conclusions can we draw? First, that the defence of home in 1947 was not a war of armies alone: it was a defence of communities, a defence of humanity. Second, that the Kashmir of that moment was plural in its defenders: Muslim, Hindu, Sikh; man and woman; professional and farmer. Third, that the sacrifice of one person is as sacred as another: in war, the hierarchy of deeds dissolves when life is given for others. Fourth, that knowing these stories helps revive the tradition of solidarity, the damaged but still meaningful notion of Kashmiri ethos and hospitality. And fifth, that remembering is an act of justice: to the fallen, to their families, and to the region’s future.

The long line of history bears witness: the invasion of October 1947 was not only a strategic gambit by one state against another; it was a crisis of civilian survival, a test of social solidarity, and a moment when Kashmir stood alone, and the people of Kashmir answered. We owe them remembrance. Their sacrifices are the foundation on which any hope for peace, pluralism and dignity in Jammu & Kashmir must be built.

When history’s focus shifts from generals to grass-roots, from military formations to neighbourhood watches and refugee tracks, we begin to see the full story: in every hidden forest path guided by a boatman or postman, in every guarded bridge, in every hospital ward lit by volunteer nurses, there lies a story of resistance and selfless service. And when a region stands alone, every act of courage, regardless of scale, shines with extraordinary light.

So let us remember: the names above, unheralded though many are, deserve our respect. Their memory is not a footnote but a foundation. And as long as the valleys echo with their silent valour, our understanding of Kashmir, its trauma, its solidarity, its courage, will be all the richer.