Written by: Rameez Makhdoomi

( The writer is an eminent freelance journalist of Jammu and Kashmir).

Introduction:

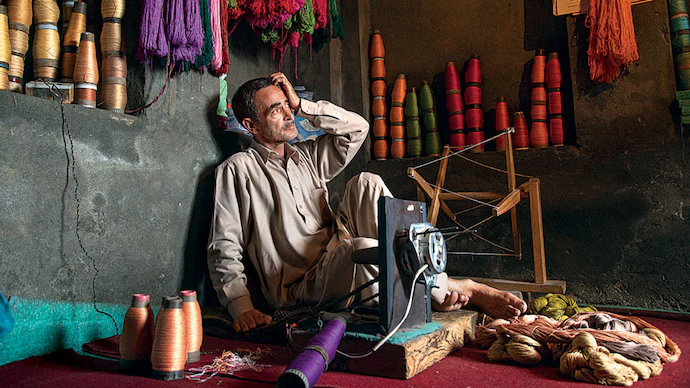

The handicrafts industry of Kashmir represents one of the most intricate and enduring artistic traditions of South Asia. It is not merely a sector of economic activity but a civilisational marker that captures the synthesis of aesthetic sensibility, spirituality, and skill. For centuries, Kashmiri crafts — from the fine weave of the pashmina shawl to the delicate carvings on walnut wood — have embodied a living dialogue between culture and livelihood. Yet, in recent decades, this once-flourishing heritage has found itself in what may aptly be called an opaque notch — a space marked by invisibility, economic uncertainty, and institutional neglect. The phrase “opaque notch” captures the contradictions within the industry: while Kashmir’s crafts are celebrated globally, the structures sustaining them remain hidden, informal, and fragile.

Despite periodic governmental initiatives and international appreciation, the craft sector faces structural opacity — of value chains, of recognition, of labour relations, and of policy vision. It is a paradoxical situation where the artisan, the true bearer of cultural capital, remains the least visible and least empowered actor in the system. This article seeks to critically analyse the current state of the handicrafts industry in Kashmir, its economic and cultural opacity, and the urgent need to reimagine it as a transparent and sustainable ecosystem.

The Legacy of Kashmir’s Handicrafts

Kashmir’s reputation as a “valley of crafts” dates back to the reign of Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (1420–1470 CE), often called Budshah for his enlightened patronage of arts and culture. His era witnessed the institutionalisation of several crafts that continue to define Kashmir’s material culture — pashmina weaving, papier-mâché, carpet-making, shawl embroidery, and wood carving [1]. Later, under the Mughals, these crafts received royal attention and became integral to Kashmir’s export identity, reaching markets as far as Persia, Central Asia, and Europe.

The British colonial period transformed handicrafts from courtly production to commercial enterprise. The establishment of the Kashmir Arts Emporium in 1911, and the trade networks through Lahore and Calcutta, globalised Kashmiri products but also introduced exploitative intermediaries. Since then, the industry has oscillated between visibility in markets and invisibility in governance — an early symptom of the opacity that now defines it [2].

Kashmir’s Major Craft Sectors: A Living Heritage

1. Pashmina Shawl Weaving

Pashmina, derived from the fine under-fleece of the Changthangi goat found in Ladakh, is perhaps the most iconic of all Kashmiri crafts. The process — from raw wool collection to spinning (yender), weaving (wonun), and embroidery (sozni) — involves over a dozen stages and multiple artisans. Yet, as per the Directorate of Handicrafts (2023), most artisans earn less than ₹10,000 per month [3]. The opacity here lies in the price asymmetry: a finished shawl may retail for ₹30,000–₹1,00,000 in Delhi or London, while the artisan receives only a fraction of that value. Middlemen, exporters, and urban traders occupy the value chain’s visible end, while the artisan remains economically invisible.

2. Carpet and Rug Weaving

Kashmir’s carpet industry, introduced from Persia during the 15th century, remains world-renowned for its knot density and design precision. Hand-knotted silk carpets from Srinagar, Budgam, and Anantnag have historically dominated export portfolios. However, government export data show a 40% decline in carpet exports between 2015 and 2022 [4]. The decline is not due to lack of demand alone, but the structural invisibility of artisans who face irregular wages, lack of social security, and competition from machine-made alternatives. Furthermore, the carpet industry has witnessed generational attrition — younger Kashmiris increasingly see no viable future in weaving due to poor remuneration and absence of recognition.

3. Papier-Mâché: The Art of Layers

Papier-mâché (kar-i-qalamdani) combines recycled paper pulp with meticulous painting to produce vases, boxes, lamps, and ornaments of intricate floral designs. This craft embodies sustainability long before it became a global buzzword. Yet, the sector faces a threefold opacity — economic (unstable markets), environmental (lack of eco-certification), and institutional (no protection for artisans from counterfeit products). Fake papier-mâché items, often made of plastic and painted in Kashmiri motifs, flood local markets, undermining authentic producers [5].

4. Walnut Wood Carving

The walnut tree (Juglans regia), locally known as doon kul, is the foundation of Kashmir’s furniture and decorative carving industry. Distinct for its rich grain and durability, Kashmiri walnut wood is globally admired. However, the craft’s survival is threatened by deforestation restrictions, export barriers, and absence of design innovation. Skilled carvers in Srinagar, Sopore, and Anantnag increasingly work as daily wage labourers for furniture dealers. The “opaque notch” manifests in their invisibility within trade statistics — while finished goods earn foreign exchange, the carver remains uncredited in both policy and profit [6].

5. Embroidery and Sozni Art

Sozni (needlework) and Tille (metallic thread embroidery) form the aesthetic heart of Kashmiri textiles. Women artisans, especially from rural districts like Budgam and Ganderbal, dominate this sector. Yet, they are doubly invisible — as informal workers and as women in a patriarchal system. The unorganised nature of their work, often conducted from home, excludes them from social protection schemes, leading to gendered economic opacity. Studies by the Craft Development Institute (CDI), Srinagar, show that women artisans contribute nearly 60% of total embroidery labour yet account for less than 20% of earnings in the value chain [7].

The Anatomy of Opacity

The “opacity” of Kashmir’s handicraft sector is not accidental but systemic, emerging as a by-product of historical exploitation, weak institutional frameworks, and market asymmetries. This opacity manifests across three interlinked dimensions: economic, cultural, and institutional. Economically, most artisans operate within an informal economy without written contracts, transparent pricing, or direct access to markets. According to the J&K Economic Survey (2022–23), over 80% of handicraft production is unregistered, making it difficult to measure or regulate [8]. Artisans depend on a layered chain of middlemen who control both procurement and sale, resulting in a near-total information gap between producer and consumer. Additionally, the proliferation of imitation goods — machine-made shawls, polyester carpets, and resin-based papier-mâché — has distorted pricing and authenticity, further deepening trade opacity. Culturally, Kashmiri crafts are widely celebrated in tourist brochures and exhibitions, yet artisans themselves remain invisible. The state’s cultural policy tends to aestheticise the products while neglecting the producers, creating a paradoxical visibility where crafts as heritage artefacts are prominent, but the social realities of artisans are obscured. This disconnect erodes intergenerational transmission, as many young artisans abandon the craft not only due to economic pressures but also due to loss of social prestige. Institutionally, opacity compounds both economic and cultural invisibility. Multiple agencies, including the Directorate of Handicrafts & Handloom, J&K Small Scale Industries Development Corporation (SICOP), and the Kashmir Arts and Crafts Emporium, exist ostensibly to support artisans. However, weak coordination between them leads to duplication of schemes, underutilisation of funds, and bureaucratic delays [9]. Audit reports by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG, 2022) highlight that beneficiary selection often lacks transparency, and allocated budgets for artisan welfare remain partially spent. Export promotion efforts are inconsistently applied; while the Export Promotion Council for Handicrafts (EPCH) facilitates market access for certain products, rural artisans, particularly women, are frequently excluded. Digitalisation initiatives such as e-Karigar and India Handmade Bazaar promise direct-to-consumer marketing, yet poor internet access, limited digital literacy, and persistent middlemen interference limit their effectiveness [10]. The cumulative effect is that the very institutions tasked with providing visibility and support paradoxically contribute to the sector’s opacity. Policies exist on paper, but fragmented execution continues to undermine artisans’ economic security and creative agency.

Decline and Challenges Across Sectors

The Kashmir handicraft sector is experiencing a multifaceted decline across various traditional crafts. In carpet weaving, artisans contend with cheaper machine-made alternatives, rising raw material costs, and diminishing skilled labour. Export data from the Ministry of Textiles show a drop from ₹700 crore in 2014–15 to under ₹400 crore in 2023–24 [11]. The social cost is equally significant, as traditional weaving families face economic precarity, and youth are increasingly disincentivised from learning the craft. Papier-mâché also faces serious challenges due to declining raw material availability, mainly lacquers and natural dyes, along with competition from plastic alternatives. Artisan numbers have reduced by nearly 60% over the last decade, and most producers lack social security or recognition [12]. This decline threatens the survival of motifs such as chinar leaves, tulips, and almond blossoms, which are emblematic of Kashmir’s visual identity. Walnut wood carving suffers from the scarcity of walnut timber and regulatory restrictions on tree felling, creating a bottleneck for artisans. Machine-made furniture from elsewhere, often marketed as “Kashmiri style,” further undermines traditional carving, and without state-backed design innovation and resource management, the craft faces a long-term sustainability crisis [13]. Embroidery, particularly Sozni and Tille work primarily done by women at home, experiences low remuneration and lack of market recognition. Machine-embroidered substitutes from other regions flood the market, diluting authenticity and causing cultural erosion as traditional designs lose relevance in modern production [14]. Pashmina shawls, despite global recognition, encounter challenges in authenticity and pricing, with counterfeit products dominating local and international markets and reducing the genuine artisan’s share of income. Although GI tagging of Kashmir pashmina in 2012 has provided some support, enforcement remains weak, and the average artisan receives less than 10% of the retail value [15].

Conflict and Market Volatility

Political instability and intermittent unrest in Kashmir have directly impacted handicrafts. Curfews, strikes, and communication shutdowns disrupt production cycles and market access. In the COVID-19 pandemic, many artisans faced complete loss of income due to delayed orders and reduced tourism. According to the J&K Handicrafts Department (2021), over 60% of artisans reported significant income reduction during periods of unrest [16].

International market volatility also poses challenges. Fluctuating foreign exchange rates, import duties, and global recessions affect exports of carpets, shawls, and papier-mâché, while small artisan-run export houses lack the capital to absorb shocks.

Technology, Digitalisation, and the Digital Divide

Digital platforms have introduced new opportunities but also highlighted inequalities. While online marketplaces can bypass middlemen, many rural artisans lack smartphones, digital literacy, and banking access. Middlemen continue to dominate e-commerce channels, posting products under their names or controlling pricing. The result is the same opaque value chain, replicated in digital form [17].

Technology can be transformative if paired with education, financial inclusion, and transparent e-market policies. QR-coded authenticity tags, online cooperative stores, and digital payment systems are steps in this direction.

Pathways to Revival: Breaking the Opaque Notch

To address the structural and moral opacity surrounding the craft sector, a comprehensive and multi-pronged approach is essential. Economic transparency must begin with the establishment of minimum wage regulations for each craft unit, monitored and enforced by artisan cooperatives to ensure fairness. Direct marketing channels through cooperatives and digital platforms should be promoted to reduce dependence on exploitative middlemen, while introducing traceability mechanisms—such as QR codes linking every product to its artisan and production details—can foster accountability and consumer trust.

Institutional reform is equally vital. A unified governing body, the Kashmir Craft Development Authority (KCDA), should be created to coordinate all artisan-related schemes and streamline administrative processes. Geographical Indication (GI) enforcement must be strengthened through laboratory certifications, consistent monitoring, and public awareness campaigns that educate consumers about authenticity. Financial support in the form of low-interest credit and targeted subsidies should be extended only to verified artisans, thereby promoting integrity within the system.

Education and skill transmission represent another key pillar. Craft education ought to be incorporated into school and university curricula to nurture appreciation and participation from an early age. Apprenticeships with stipends can encourage youth engagement, while structured collaborations between designers and artisans can stimulate innovation without compromising traditional aesthetics or techniques.

Gender inclusion is also imperative. Women-led craft cooperatives should be established with legal recognition and access to social security benefits, ensuring equitable participation in the economic and creative domains. Furthermore, documenting oral histories and traditional knowledge can help preserve the intangible cultural capital passed through generations of women artisans.

Sustainable resource management must support this ecosystem. Initiatives such as walnut tree replantation programs, ethical pashmina sourcing, and the use of eco-friendly dyes and materials can align craft production with international environmental standards. Community forestry programs can also link artisans’ livelihoods directly to sustainable resource use, fostering long-term ecological and economic resilience.

Finally, cultural diplomacy can elevate Kashmir’s crafts on both national and global stages. International exhibitions that foreground artisan narratives, partnerships with UNESCO to safeguard Kashmir’s crafts as Intangible Cultural Heritage, and domestic campaigns encouraging consumers to purchase certified handmade products can collectively enhance recognition, ethical consumption, and pride in the region’s artisanal legacy.

Conclusion: Beyond Economics

Kashmir’s handicrafts stand at a crossroads between commercialisation and cultural preservation. The prevailing “opaque notch” is not merely an economic issue but a moral and civilisational one. Artisans, though central to sustaining Kashmir’s identity, remain largely invisible in markets and policy frameworks. Recognising and rewarding their contribution is therefore both an economic and an ethical imperative. Transparency becomes the first step toward restoring dignity, fairness, and continuity in this endangered sector.

The handicrafts industry of Kashmir—long celebrated as a symbol of beauty, skill, and cultural continuity—now operates within layers of economic exploitation, cultural invisibility, and institutional neglect. Crafts such as carpet weaving, papier-mâché, wood carving, embroidery, and pashmina shawls continue to captivate global admiration, yet the artisans behind them struggle for survival and recognition.

Revitalising this sector demands more than piecemeal policy reforms; it calls for a comprehensive and ethical engagement with the artisans themselves. Systemic interventions such as transparent pricing, institutional coordination, digital empowerment, gender inclusivity, sustainable resource management, and cultural recognition must form the core of revival efforts. Crucially, this transformation requires viewing the artisan not as a mere labourer, but as the custodian of a living tradition and the bearer of collective memory. Only through such integrated action can Kashmir’s handicrafts endure—not as relics confined to museums, but as vibrant, visible, and dignified expressions of the Valley’s economy, culture, and identity.

References

- EPCH (2023). E-commerce Participation and Market Access Study for Handicrafts in Kashmir.

2. Government of Jammu & Kashmir, Economic Survey 2023–24, Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Srinagar.

3. Khan, F. A. (2019). Craft Heritage of Kashmir: Continuity and Change. Srinagar: Gulshan Books.

4. Directorate of Handicrafts and Handloom (2023). Artisan Income and Production Report, Srinagar.

5. Ministry of Textiles, Government of India (2023). Export Data on Indian Carpets and Shawls.

6. Craft Revival Trust (2022). Papier-Mâché of Kashmir: Challenges and Sustainability, New Delhi.

7. J&K Forest Department (2021). Walnut Timber and Handicrafts Sustainability Report.

8. Central University of Kashmir (2022). Survey on Women Artisans in Kashmir.

09. Economic Survey of J&K (2022–23), Directorate of Economics & Statistics.

10. Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India (2022). Performance Audit of Handicrafts Schemes in J&K.

11. Indian Institute of Entrepreneurship (2023). Digital Empowerment in Handicrafts: A Field Study from Kashmir.

12. Ministry of Textiles (2023). Annual Report on Carpet Exports, 2014–2023.

13. Craft Revival Trust (2022). Decline of Papier-Mâché in Kashmir.

14. Ahmad, S. (2022). “Sustainability Challenges in Walnut Wood Carving.” Journal of Himalayan Studies, Vol. 12(2), pp. 45–58.

15. Economic Times (2023). “Machine Embroidery Floods Kashmiri Markets.” ET Handicraft Edition, July 2023.

16. Wool and Woollens Export Promotion Council (WWEPC, 2022). Pashmina Export Review.

17. J&K Handicrafts Department (2021). Impact of Political Instability on Artisan Livelihoods.