BY: Ummer Ishaq Bhat

In a quiet and serene village of Kaprin, nestled in the orchards and streams of south Kashmir’s Shopian district, kashmiri literature found one of its most devoted guardians—Naji Munawar. He is known to the world of writers by his pen name but born as Ghulam Nabi Lone in 1934, he lived a life where poetry was not a profession but a way of protecting memory, identity, and innocence. For Kashmiri children he became a gentle guide; to scholars, he was a preserver of heritage; and to his fellow villagers, he was a proud custodian of tradition.

Munawar’s earliest lessons came not from formal classrooms but from his own home. His father, a man with deep faith in learning, converted their modest house into a small village school. Little Ghulam Nabi was its very first student. In that home school he absorbed not just letters and numbers but also the idea that education must be liberally equal in the community for all. He sought his formal education in Government High School, Shopian, where he sat alongside with those classmates who later themselves grew into prominent voices such as journalist (poet) Shameem Ahmad Shameem and literary historian Mohammad Yousuf Taing. In those school years he shaped his intellect, let himself grounded in Kashmiri soil while also opening windows to broader conversations of literature, culture, and politics.

Choosing the path of teaching, Munawar’s first posting carried him far away from Shopian—to Ladakh, a land of barren landscapes and rugged beauty. The distance from his homeland only sharpened his imagination. To teach young students in that unfamiliar and remote land deepened his conviction that education should never be limited to rote learning. For him, true teaching and learning meant awakening curiosity, shaping values and connecting children to their cultural basic roots. This philosophy soon spilled into poetry, and he began writing verses not just for adults but, most memorably, for children.

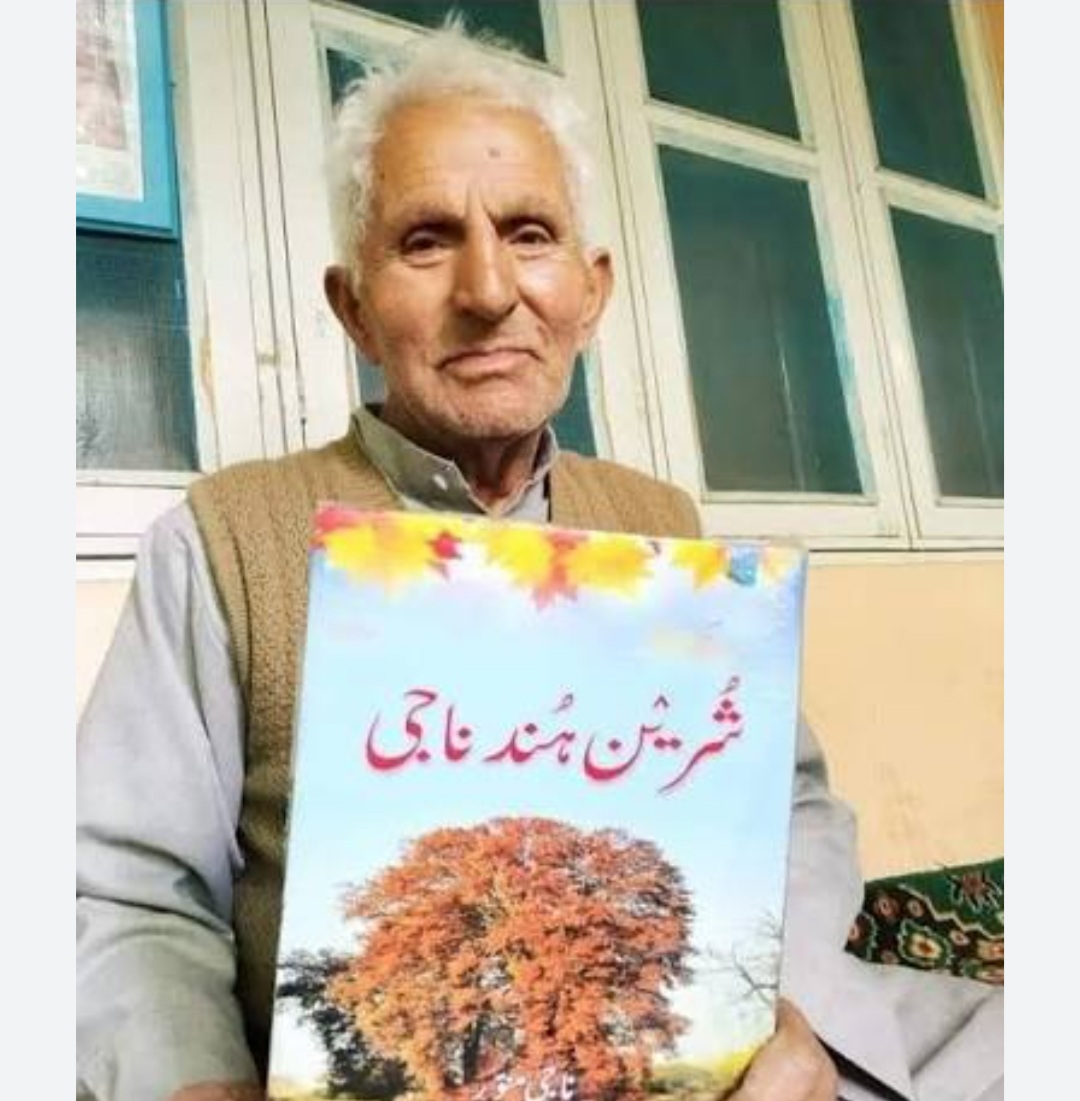

In 1959, Munawar’s first book for children Mokhte Laer was published. It marked the beginning of a literary journey that transformed Kashmiri children’s literature. His words were playful yet powerful, giving ways to honesty, kindness and respect through simple rhymes and humorous imagery. Over the decades, he wrote a series of works that delighted and influenced young readers. The following Shuren Hund Luki Baith, Shuren Hund Iqbal, Dunyihchi Daleela, and finally his celebrated collection Shuren Hund Naji which was published in 2017. His last book which is a collection of 54 poems and 99 riddles became a fixture in Kashmiri school libraries. For generations of children his riddles are more than word games or tongue twisters yet they are playful doors to language, imagination, and identity.

What distinguished Munawar was the dignity with which he treated his young audience. He never wrote down to children; instead, he trusted them as intelligent readers. This respect made his poems timeless, keeping them alive across generations.

Although celebrated as the “poet of Kashmiri childhood,” Munawar’s creativity extended well beyond children’s verse. His anthology Naag Raat (1974) displayed his lyrical skill in romantic poetry. He also played a pioneering role in introducing Kashmiri readers to world literature through translations. Works like Shakespeare’s King Lear and Julius Caesar, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, and selected poetry of Allama Iqbal (Partavi Iqbal) entered Kashmiri through his pen. In doing so, he connected his language to universal traditions, enriching both sides.

Munawar’s contributions were not only confined to the realm of poetry. He had devoted himself in preserving the literary heritage of Kashmir valley. He compiled and edited the collected works of great Kashmiri scholars like Mahmud Gami and Sheikh-ul-Alam (RA), ensuring that their words should remain accessible to the contemporary readers. Naji with his brother, the noted writer Shafi Shouq, has co-authored Kaeshir Adbuk Tavarikh a landmark in the history of Kashmiri literature.

His passion for heritage went beyond books. Munawar gathered coins, terracotta artefacts, carved stones, and old tools that carried stories of Kashmiri life. He has curated these in a small private museum (home) in Kaprin turning his love for tradition into a living treasure for his community.

Recognition came steadily but never defined him truly. In 2002 he received the Sahitya Akademi Award for Pursaan, a scholarly collection of essays on forgotten poets and cultural traditions. In 2019 he was awarded the Bal Sahitya Puraskar for Shuren Hund Naji. Each award was a reminder of his dual identity both a poet of innocence and a custodian of heritage.

In 2022 University of Kashmir tributed him by celebrating “Naji Munawar Day”, honouring his lifelong dedication to literature, education, and cultural preservation.

Even in his eighties Munawar’s pen continued to flow like water in a sea. He guided young writers, maintained his personal library by editing and composing works and often welcomed visitors to his utopic museum(home). In 2021 at the age of 86 he passed away in his beloved home at Kaprin. His departure left a deep void not only in Kashmiri literature but also in the cultural memory of his homeland. His loss as a writer perhaps will never be compensated. Many writers and different people have expressed their deepest concern over his death as a great loss for kashmiri literature. Famous CPI leader Yousuf Tarigami expresses his grief over the death of Munawar. He says, “Munawar was legendary, unparralled scholar, a preface of the history of kashmiri language and literature. He was a linguist, critic and a great historian.”

Today his poems continue to echo in classrooms his riddles still spark curiosity among children and his scholarly works remain essiential to the students of Kashmiri literature. To the people of Kaprin he is a source of pride, to readers a companion of innocence and to Kashmiri culture, a bridge that connects the past to the future.

Naji Munawar’s true legacy lies not only in the books that he wrote but in the bridge that he built between children and tradition, Kashmir and the whole world and finally between memory and imagination. He showed that literature is not just about expression but also about preservation of culture and tradition, transmission and renewal. Through his life and works, the laughter of Kashmiri children continues to carry the echoes of their land, particularly their language, and heritage.