By: Irshad Ahmad ( Research scholar )

Jammu and Kashmir is passing through a moment of deep political change — from a place once synonymous with unending conflict and cycles of violence to one where law and order form the foundation of public life. This transformation reflects a conscious shift in the Union’s policy: standing with victims of terror while steadily dismantling the entrenched networks that once sustained the conflict economy. By reordering priorities in both physical space and civic life towards the collective good, the scaffolding of violence is being stripped away. In the process, the state is no longer only asserting its authority but also correcting long-standing injustices and reshaping the political order in lasting ways.

In every functioning democracy, recognising and mourning those lost to terror is more than a ritual — it is a matter of political ethics. It signals the living bond between the state and its people, a bond that cuts across party lines and cultural divides. As Judith Butler has written, the way grief is framed shows “whose lives are considered grievable” and “whose are rendered invisible.” A policy for terror victims changes that equation by treating all losses equally — regardless of place, politics, faith, or identity — ensuring they remain part of the nation’s collective memory.

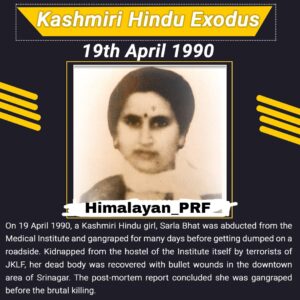

For decades, critics in Jammu and Kashmir have painted the Indian state as harsh or indifferent. After the turbulence of the 1990s, families of civilians killed by militants were often left without acknowledgement, absent from official records and symbolic recognition. That silence deepened the moral scars of conflict. As Sumantra Bose observed, neglecting these lives allowed anti-state narratives to claim the government lacked moral legitimacy. In 2025, the Lieutenant Governor moved to end that neglect, bringing in a policy framework that joined targeted welfare measures with digital systems to make sure these families were part of the formal machinery of governance.

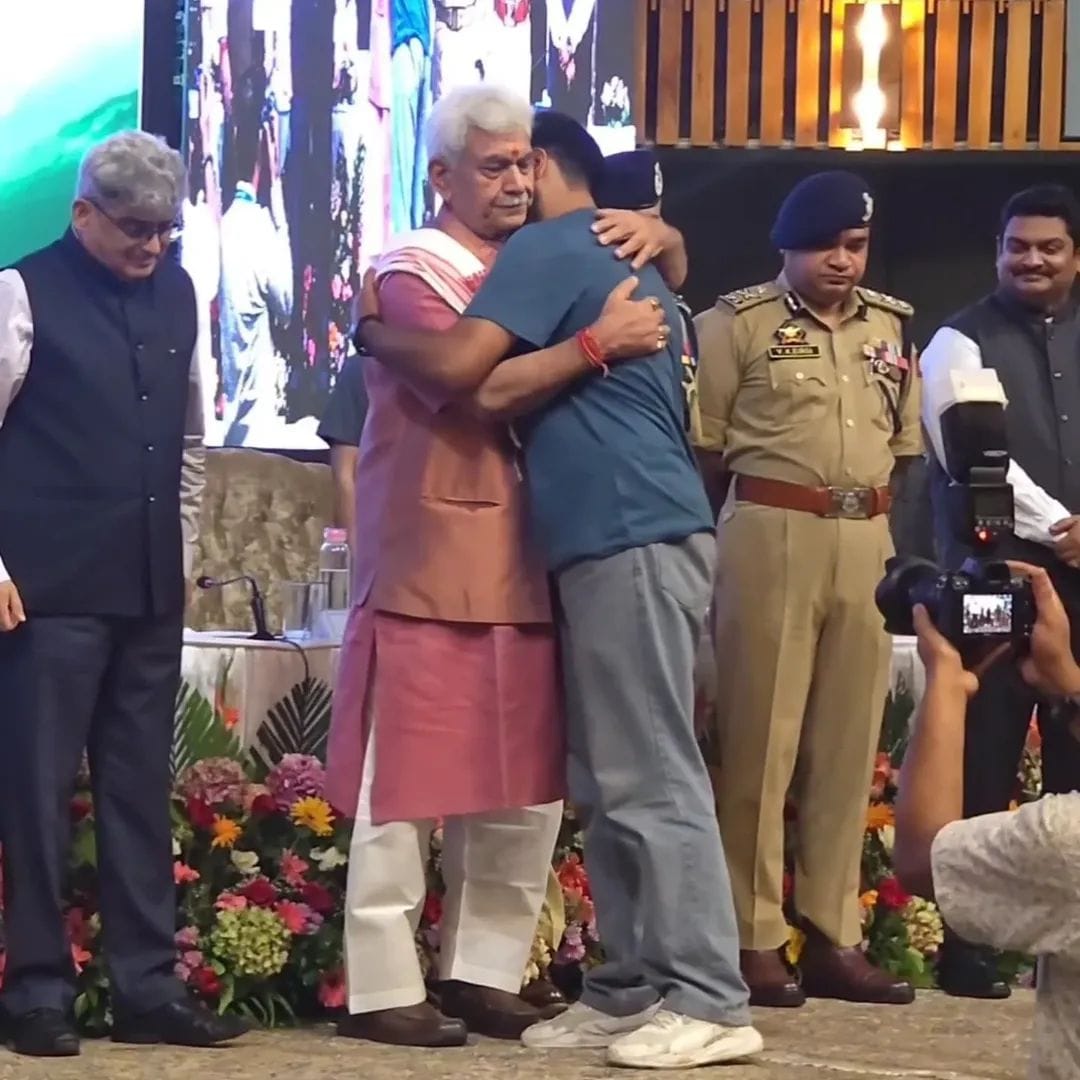

On 29 June 2025, during a visit to Anantnag, the L-G promised that eligible next-of-kin of terror victims would be given government jobs within 30 days. Less than a fortnight later, forty such families in Baramulla received appointment letters. A dedicated online portal was launched on 23 July to register grievances, track compensation, resolve property disputes, and process employment applications. Helplines were opened in both Jammu and Kashmir divisions, and special monitoring cells were set up in the offices of the DGP, the Chief Secretary, and at district headquarters. At the SKICC in Srinagar, the L-G handed over more than 200 appointment letters, underlining his commitment to see the policy through. The Save Youth Save Future Foundation played a crucial role in identifying cases, compiling data, and pressing for the policy, helping turn its aims into real opportunities for young people.

By publicly recognising these families, giving them jobs, and restoring properties, the administration sends a clear counter-message: these lives count, and the state is with them. Speaking in Baramulla, the L-G said, “terror victim families, forsaken and forgotten, suffered silently” for decades — and his government was now bringing their voices into the open while challenging “conflict entrepreneurs” who had twisted the past.

For years, J&K’s political memory has been shaped by selective remembrance, where victims of militant violence often went unacknowledged. That omission created space for hostile narratives to grow. Aleida Assmann’s concept of “cultural memory” shows that recognition is an act of justice, weaving suffering into the state’s permanent institutional and symbolic fabric. These moments are more than service delivery — they are the writing of memory into public record, turning private grief into a shared account of history.

Sociologist Jeffrey Alexander points out that when public institutions acknowledge trauma, they strip power from those who try to downplay it. Unlike earlier approaches that placed victim aid below security priorities, this policy lifts victims from the condition of homo sacer — bare existence — into citizens whose dignity is guarded by law, welfare, and public honour.

Carl Schmitt described sovereignty as the authority to decide on the exception. In J&K, this has often meant granting counter-insurgency forces extended powers. The Terror Victim Policy turns that logic around, using the “exception” to include rather than exclude. It is a form of “redemptive security” — not only deterring violence but restoring moral balance. The state’s image shifts from that of an enforcer to that of a guarantor of dignity, undermining the insurgent claim that it exists only to control.

As Barry Buzan and colleagues have argued, securitisation occurs when an issue is raised to existential priority. In this policy, remembering becomes a moral duty, and forgetting a moral threat. Cultural memory is thus protected alongside land and life. The approach replaces “violence for violence” with “narrative for narrative.” More than a welfare scheme, it is a deliberate rewriting of the public record, placing the state as protector rather than oppressor. Done inclusively, it can change both the lives of victim families and the historical telling of the conflict.

The initiative is also shaping the outlook of the young. Watching the state recognise and honour victims builds trust in governance and renews a sense of civic duty. It fosters a generation that values justice, accountability, and empathy — future leaders ready to rebuild the moral and social fabric of their communities.

The administration’s lasting contributions are the opening of a new political era, the repair of long-ignored injustices, and the formal recognition of those who bore the brunt of terror. Under Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha, governance has moved from neglect to recognition, from passive remembrance to the active institutionalising of collective memory. Its guiding message is clear: those who stood for the state must be supported and honoured. This is a framework where administrative precision, moral obligation, and welfare delivery meet in the service of justice.