By: Vats Ambardar ( junior Research Fellow )

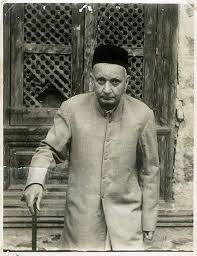

In the intellectual and spiritual annals of Kashmir, where silence has often carried more weight than speech, and where poetry has often borne the burden of philosophy, few fi gures resonate with the depth and quiet gravitas of Zinda Koul. Known reverently as “MasterJi,” Koul was not simply a poet, educator, or translator. He was an ethical and civilizational sensibility—an interpreter of Kashmir’s metaphysical discourse, who, through words and silences alike, sought to retrieve a moral imagination slowly disfi gured by modernity, colonial intrusion, and sectarian abstraction.

To situate Zinda Koul within a merely biographical frame is to miss the profundity of his contribution. His life unfolded not merely in historical time but in philosophical time—in the twilight between cultural inheritance and epistemic rupture. Born in 1884 in Habbakadal, a linguistically rich and spiritually syncretic locality in Srinagar, Koul came of age in Kashmir undergoing a gradual, if often painful, transformation under Dogra rule. The political landscape was marked by administrative autocracy and structural exclusions, but the deeper crisis was spiritual and epistemological: a growing disjunction between the inherited traditions of thought and the alienating imperatives of a colonially induced modernity.

Koul’s early years were shaped by a uniquely Kashmiri intellectual milieu where Sanskritic learning, Persian poetics, Islamic mysticism, and indigenous Shaiva metaphysics cohabited in complex yet organic tension. He grew up not within a monoculture of thought but amidst a polyphonic civilization—where the Upanishads conversed with the Masnavi, where Lal Ded’s vakhs could be invoked in the same breath as Nund Rishi’s shruks, and where metaphysical inquiry was inseparable from ethical orientation. This was not secularism in the modern statist sense, nor was it a superfi cial syncretism for display. It was an ontological pluralism—an understanding that truth, though one, reveals itself through multiplicity.

Against this backdrop, Koul emerged as both a product and a critic of his time. While many of his contemporaries were absorbed by the lure of colonial bureaucracies or nationalist polemics, Koul chose the less glamorous, more exacting path of introspective labor. His pursuit of language was not utilitarian but civilizational. Fluent in Kashmiri, Sanskrit, Urdu, Persian, Hindi, and English, he did not wield languages for embellishment or display but treated each tongue as a vessel of metaphysical insight. Language, for Koul, was not merely a system of signs but a moral universe—one that demanded attunement, reverence, and restraint. It is perhaps this disposition that made him one of the earliest and most profound literary translators of Kashmir’s spiritual heritage.

His 1924 work Kashmiri Lyrics, published in Allahabad, stands as a landmark in the history of Indian literary translation—not for its formal innovation, but for its philosophical fi delity. In rendering the mystical utterances of Lal Ded and Nund Rishi into English, Koul was not engaged in a benign literary exercise. He was, in eff ect, rescuing a civilizational voice from the twin perils of insularity and oblivion. His translations were acts of metaphysical interpretation. They did not domesticate the mystical into the language of empire, nor did they exoticize the local for foreign consumption. Instead, they invited the reader—whether Kashmiri, Indian, or global—into the inner sanctum of Kashmir’s spiritual grammar.

But to regard Koul solely through his writings is to miss the ethical force of his pedagogy. For decades, he served in the Government Education Department, earning the aff ectionate title “MasterJi” among generations of students. Yet there was nothing conventional about his teaching. In a society slowly succumbing to bureaucratic formalism and mechanical instruction, Koul’s classroom was a rare site of moral seriousness. Literature, under his tutelage, was not merely a subject to be memorized but a portal to self-interrogation. He deployed verse and parable, silence and speech, not to enforce doctrine but to awaken the intellect and orient it toward the good. His pedagogy, in that sense, was not derivative of Enlightenment rationalism nor pre-modern scholasticism—it was a distinctively Kashmiri fusion, rooted in the Vedantic pursuit of jnana, the Sufi ethic of tahqiq, and the Shaiva discipline of pratyabhijna.

Zinda Koul’s original poetry, especially in the Kashmiri collection Sumran—a term meaning remembrance or meditative contemplation—off ers an extraordinary window into his philosophical interiority. Unlike the fl orid and sometimes indulgent lyricism characteristic of romantic poetry, Koul’s verses are marked by austerity. There is an economy of language, a deliberate refusal to embellish, as though each word were the residue of an intense inner distillation. Thematically, his poetry navigates the terrain of non-duality, impermanence, divine longing, and ego-eff acement. But more than thematic content, it is the moral atmosphere of the poetry that distinguishes it. Koul does not seek to persuade; he invites. He does not seek to explain; he evokes. He does not shout truths from rooftops; he whispers them into the soul’s ear.

Underlying his literary and pedagogical work was a deeper civilizational impulse: the preservation of Kashmir’s syncretic ethos against the encroachments of reductionist ideologies—both colonial and nativist. Koul was acutely aware that the great traditions of Kashmir—Shaivism, Sufi sm, Bhakti, and Vedanta—had sustained a cultural ecology of profound pluralism. He also understood that this ecology was imperiled, not just by external political forces but by internal amnesia. His life’s work, then, can be read as a sustained philosophical resistance to the fl attening of Kashmiri identity into exclusivist paradigms.

That he received the Padma Shri in 1956 was a rare, though insuffi cient, acknowledgment of his contribution. In a postcolonial polity still enthralled by the grammar of nationalism and institutional power, the moral authority of a quiet, unmarried schoolteacher-poet in the margins of Srinagar was easy to overlook. Yet one suspects that Koul himself remained unperturbed. His ethical compass did not pivot on recognition but on fi delity—to truth, to silence, to the arduous labour of self-knowing.

He spent his fi nal years much like his earlier ones—in solitude, reading scriptures, writing poetry, and mentoring young minds. There was no performative asceticism, no rhetorical disdain for the world. There was, instead, a quiet dignity—a stillness that bore witness to an inner clarity. He passed away in 1965, leaving behind no

political treatise, no institution, no mass movement. And yet, his absence remains more present than the presence of many who claim to speak for Kashmir today.

To refl ect on Zinda Koul in the present moment is not a nostalgic indulgence. It is a philosophical imperative. In a world increasingly fragmented by narrow identities and algorithmic banalities, where spiritual vocabulary has been replaced by ideological sloganeering, Koul off ers a diff erent grammar of engagement—one that is rooted in contemplation, sustained by plurality, and oriented toward transcendence. He reminds us that culture is not what we perform, but what we preserve; that knowledge is not accumulation, but recognition; and that peace is not the absence of confl ict, but the presence of moral clarity.

The contemporary neglect of Koul is symptomatic of a deeper malaise—the marginalization of those voices that do not conform to the idioms of our time, that refuse to shout, that demand silence before they speak. And yet, precisely in that silence lies his enduring power. For Koul’s voice does not echo in public squares; it resonates in inner chambers. His legacy cannot be instrumentalized; it must be meditated upon. And in a world fatigued by noise, that may be the most radical off ering of all.

As he once wrote, with devastating simplicity: “Let not the noise of the world drown your inner song. In silence, truth reveals itself.” This is not a poetic fl ourish; it is a philosophical provocation. One that beckons us—not toward Zinda Koul the man, but toward the ethical and spiritual labour that his life continues to demand of us.