By: Dr Zahid (Independent Researcher: PhD in Political Science)

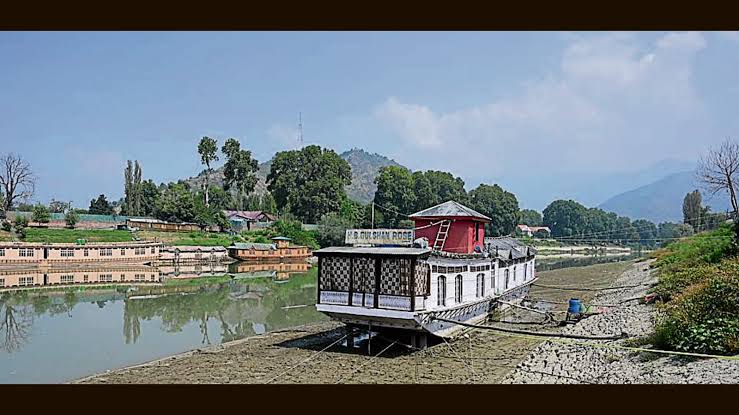

There are elements in a society’s life so vital, so intimate, that their loss goes unnoticed until the very rhythm of collective existence begins to falter. Water is such an element. In Kashmir, where mountains meet memory and rivers flow like verses of an ancient hymn, water is not just a resource — it is the essence of life, livelihood, and identity. Water once flowed not merely across land, but across generations. It threaded villages and kinships, customs and rhythms, shaping a landscape where every spring (Nag) was a symbol of continuity and every irrigation channel (Kul) a promise of community. And now?

Today, I ask — not with bitterness, but with aching clarity — where have the waters gone?

In my own area, a place once cradled by abundance, there were five, ten, sometimes even more Nags in every village. Some gurgled in courtyards, others murmured at the foot of mountains, and a few served as sacred spaces where women filled copper vessels and children learnt reverence. The Kuls branched from these Nags, flowing into orchards and paddy fields, and every villager knew when it was their turn to divert or clean. It was an unwritten pact. Water was not owned; it was respected.

Today, hardly any Nag flows sustainably. The Kuls are dry or broken. The springs are choked or buried under concrete. Those that remain are seasonal, neglected, polluted. We are not just losing water; we are losing memory.

And the question that stirs like silt beneath these dry beds is this: How did we forget to care for what cared for us?

Water as Memory, Water as Moral Compass

To speak of water is to speak of time. It carries the echo of rituals, the murmur of folklore, and the moral clarity of stewardship. But when water is reduced to utility — to taps, tanks, and pipelines — it becomes mute. What we face in Kashmir is not just a water crisis. It is a crisis of consciousness.

The philosopher Gaston Bachelard once wrote, “Water is the most intimate substance… It surrounds us, it reflects us, it becomes us.” But what does it reflect now? Dry fields. Clogged ponds. Villagers lining up for tanker supply. And perhaps more tragically — indifference.

We once lived in a civilisation of water, not a society of consumers. Our elders didn’t need seminars to understand rainwater harvesting; they built Zamindari Kuls with bare hands. They didn’t need SDGs or sustainability goals; they passed on the practice of cleaning the Nag before every festival, of planting a tree near every stream.

Where is that wisdom now?

Where are the youth who once sat with their grandmothers beside the Nag, listening to the stories of how the village came to be named after that very spring?

Where are the men who would rise at dawn to open the Kul for the neighbour’s field before their own?

Where are the women who taught that wasting water was a sin before it became an environmental concern?

What kind of development allows us to forget the springs under our feet while discussing satellites in the sky?

Kashmir: The Water Bowl That Forgot Itself

There was a time when Kashmir was called the “water bowl of the Himalayas.” Glacial melt, monsoon rains, alpine lakes, and a network of springs made it a self-sufficient, lush ecological basin. The ancient texts — from Nilamata Purana to local oral epics — testify to this watery abundance. Even Walter Lawrence speak of Kashmir’s rich hydrography, where no village was ever too far from water.

But what has modernity done?

We have allowed the language of efficiency to silence the language of reverence. We have traded the humility of springs for the arrogance of borewells. We have lost the pause — that sacred space between need and excess. And we continue to plan without listening — to the land, to the people, to the memory of flowing water.

Climate change has only accelerated this forgetting. Snowfall patterns have changed. Glaciers are melting unpredictably. Springs are drying earlier each year. The 2014 floods and current erratic droughts are not simply meteorological events — they are ecological revelations. They warned us: when water leaves your memory, it will also leave your soil.

And now the water bowl is cracked.

Revival Is Not Nostalgia. It Is Resistance.

But this is not a lament. It is a call.

Reviving the Nag-Kul system is not a retreat into the past. It is a leap into a more rooted future. A future where the community becomes the custodian again — not waiting for tenders and contractors, but rising in quiet, determined stewardship.

In every village, can we not:

- Identify the old Nags and protect them with stone linings and seasonal cleanings?

- Map and restore Kuls with youth brigades, farmers’ cooperatives, and schools?

- Celebrate “water days” not with plastic banners but with collective work and reflection?

- Make water part of our storytelling, poetry, and pedagogy again?

Philosopher Ivan Illich wrote, “The future depends less on what we invent and more on what we remember.” In Kashmir, remembering water is remembering ourselves.

Let us not seek convenience in blame. Let us dare to ask:

- Why do we complain of water scarcity but let the Nag beside our mosque or temple be turned into a garbage pit?

- Why do we speak of global warming but never discuss localised over-extraction from our aquifers?

- Why do we teach our children physics or chemistry but not how to follow a stream to its source?

- Why do we allow hotels and houses to be built on old springs — then cry over falling water tables?

Are we becoming a society which can survive without reverence?

Women, Youth, and the Moral Rebirth of the Commons

The way forward lies not in blueprints but in moral imagination. Let the women, who have carried the water pots and washed the rice at the Nag, be brought to the planning tables. Let the youth, who search for meaning in uncertain times, be engaged not just as volunteers but as water-keepers. Let faith leaders, who once invoked water in sermons, speak again of purity and waste, of springs and sins.

And above all, let the village become a space of repair — not just of pipes and canals, but of the broken bond between earth and ethics.

A Kashmir of Springs Is Still Possible

Let us not despair. Kashmir still breathes. There are villages where old men speak of how water once flowed, and children listen. There are schoolteachers who walk students to half-dead springs and speak of life. There are mothers who collect extra rainwater and whisper that this is what their mothers taught them.

The soul of Kashmir is not dry yet. It waits. Let us return to it. Let us cleanse not just the Nag but the negligence around it. Let us repair not just the Kul but the covenant that made it sacred. As Rumi says,

“Don’t get lost in your pain, know that one day your pain will become your cure.”

Let the dry spring become our teacher. Let the absence remind us of presence. Let the silence of the water be filled again with voices — not of protest alone, but of promise.

To Will the Waters Back

Soren Kierkegaard wrote, “Purity of heart is to will one thing.” Can we will, with purity, the return of the waters — not for commerce or comfort, but for conscience?

Socio-economic development in Kashmir must begin with spiritual realignment. It is not just about electricity, dams, and pipelines. It is about living with water, not just using it. It is about rebuilding not just infrastructure, but intimacy.

Let every spring we restore be a stand we take.

Let every Kul we revive be a story we remember.

Let every drop we save be a witness to our return.

Let the land say:

They remembered. And the water came back.