By : Rakesh Kaul

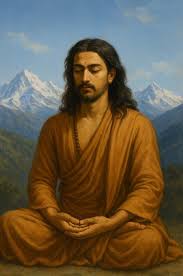

Once called Sharada Desh—the Land of Wisdom—Kashmir was not merely a geographic valley but a luminous field of consciousness. Long before its name became synonymous with conflict, it radiated the most profound metaphysical insights of the human spirit. The peaks surrounding it were not just majestic—they were teachers. Its rivers did not merely water the land—they irrigated the soul. The Gods resided on the mountain peaks, the Goddesses in the rivers and springs. In an era increasingly haunted by technological excess, social alienation, violent conflicts, and ecological disintegration, Kashmir’s transcendental knowledge offers more than solace—it offers strategy: a path not just inward, but forward. A path that one gravitates to naturally if there is the pre-requisite of the state of swatantra, freedom, which in itself is the pre-requisite to achieving bliss.

What makes Kashmir unique is that it transformed its setting into its spiritual practice, or sadhana. The beautiful forests, snows, rivers, and skies became mirrors for the inner Self. Unlike renunciatory traditions that devalue the world, Kashmir Shaivism celebrates it as Shiva’s dance. In its vision, liberation (moksha) is not withdrawal but participation—with full awareness-in the divine play of reality. The goal in life was jivanmukti, complete worldly fulfillment and liberation while alive. The hardest thing to achieve in life, equipoise, was the hallmark of its people, the Kashmiris. The foundational texts—Vijnana Bhairava Tantra, Spanda Karikas, and Pratyabhijna Hridayam—map inner states with a precision rivaling that of any modern neuroscience. They are not abstract philosophies but guidebooks for lived transcendentalism.

Kashmir’s tantric traditions placed the feminine divine (Shakti) at the center of spiritual experience. The energy of awakening was not a masculine suppression of emotion, but a feminine integration of polarity. The sacred feminine was not behind the throne—it was the throne. Kashmir became home to an unparalleled lineage of Shakti worship, from Tripura Sundari to Ragnya Devi (Kheer Bhawani). Its key benefit was an unparalleled flowering of creativity and innovation. In the first millennium and earlier, the Kashmir Valley was to technology what Silicon Valley is today. The only difference is that Kashmiri technologies never get obsolete. But it also created a society of great female empowerment and kindness. As Lalla said, “Selflessness is the Self revealing itself.” This emphasis on the feminine finds echoes today in global movements toward embodied healing, intuitive leadership, and ecological stewardship—areas where Shakti’s lessons are more relevant than ever.

The Civilizational Impact Beyond Borders

Kashmir was never a cul-de-sac of culture. It was a radiant point on the Silk Road of Ideas—a transmitter of transcendental insight across the roof of the world. Kashmiri monks, scholars, and translators significantly influenced the development of Buddhist academies in Khotan, Bamiyan, and Dunhuang. The renowned Ratnakarashanti, Vimalamitra, and Gunaprabha traveled from Kashmir to Bactria and Tibet, carrying with them the tantric and Yogachara doctrines that are foundational to Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism, as we know it, is deeply indebted to Kashmiri intellectual and ritual lineages. The translation movement at Samye Monastery, under the aegis of Padmasambhava and Santarakshita, relied heavily on Kashmiri intermediaries. Kashmir’s syncretic vision helped Tibet fuse tantra with monastic discipline. In Nepal, the Newar Vajrayana tradition also bears the imprint of Kashmiri Shaiva iconography, cosmology, and aesthetics, as evident in temple architecture, ritual mandalas, and philosophical texts.

The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang extolled Kashmiri scholars as among the most refined in the Buddhist world. The Shiva Sutras’ meditative techniques later found resonance in Chan and Zen. The aesthetic philosophy of rasa, developed in Kashmir, had a profound influence on Japanese Noh theatre and the concept of yūgen—mystery and depth that transcends words.

In the early 20th century, scholars such as Sir John Woodroffe (also known as Arthur Avalon) and Swami Lakshman Joo introduced Kashmir Shaivism to Western audiences, influencing thinkers ranging from Aldous Huxley to Carl Jung. Pandit Gopi Krishna was the foremost modern exponent of Kundalini Yoga in the West. Today, fragments of this wisdom animate global yoga, mindfulness, and consciousness studies.

A Culture of Inquiry and Freedom

Kashmir nurtured a pluralism of thought unmatched in its time. Its thinkers debated Buddhists, Vedantins, Jains, and Mimamsakas—not to defeat them, but to refine their ideas. Utpaladeva and Abhinavagupta were both mystics and logicians. Their works—especially Tantraloka and Ishvarapratyabhijna Karikas—present a metaphysical framework in which aesthetic joy, intellectual clarity, and mystical experience form a seamless continuum. The valley was not merely sacred—it was a university of the soul.

But this light was dimmed. The cultural erasure and forced exodus of Kashmiri Pandits in 1989–1990 was not merely a humanitarian crisis—it was a civilizational wound. The exodus fractured the custodianship of texts, rituals, oral traditions, and sacred sites. The Shakti temples fell silent, the gurus vanished, and the manuscripts lay abandoned. What was lost was not only territory but the continuity of the world’s most refined transcendental tradition. As Western seekers embrace diluted versions of meditation and yoga, they unknowingly sip from a spring whose source has been cut off from its own people.

Reclaiming the Sacred Thread: Empowerment as Prerequisite

The resurgence of Kashmir’s wisdom cannot be outsourced or abstracted. It must begin with the people who embodied it. The Kashmiri Pandits are not just a community in exile—they are trustees of a knowledge system. Justice for them is not only political restitution—it is spiritual continuity. Reviving the temples, rebuilding the study centers, returning access to shrines like Sharada Peeth, and restoring the right to live and worship freely are not parochial demands—they are civilizational imperatives. No sustainable spiritual resurgence is possible without repairing the broken vessel that once carried the sacred light.

If Nalanda symbolized India’s Buddhist intellect, then Sharada Peeth symbolized its tantric genius. Its reconstruction—physical, symbolic, and pedagogical—can become India’s gift to the world. Imagine a New Sharada Peeth—a center for consciousness studies, comparative spirituality, and ecological ethics—rooted in Kashmiri Shaiva-tantra, open to the world, and stewarded by those with ancestral lineage and lived wisdom. It would build on the small temple newly constructed in Tithwal. Such a place could teach not only meditation but also how to live: with joy, with clarity, and with reverence.

The Himalayan Mandala: A Geopolitical and Spiritual Imperative

The Himalayan region stands at a precarious crossroads today. Strategic competition between regional powers—India, China, and others—unfolds not just on icy ridgelines, but in the hearts and histories of the peoples who dwell along this sacred arc. In this tense landscape, a civilizational approach to diplomacy is urgently needed—one that fosters unity rather than division. Kashmir, with its unparalleled legacy of transcendental synthesis, holds the key. It can serve as India’s soft power pivot—a spiritual and cultural re-connector to the Himalayan peoples of Ladakh, Nepal, Tibet, and Bhutan. These regions share a substratum of tantric, yogic, and Shaiva-Buddhist values that once flowed freely from Kashmir’s great centers of learning. Reanimating this shared heritage could create a Himalayan mandala of mutual respect and civilizational unity. India’s revival of its Kashmiri connections—beginning with the restoration of the Kashmiri Pandit community and their sacred sites—will not only serve justice but signal a civilizational reawakening. It can become a counterpoint to coercive statecraft: a diplomacy of the spirit, rooted in shared metaphysical values rather than militarized borders.

Conclusion:

Kashmir was not only the Abode of Shiva—it was the summit of the Indian spirit. In its snows and silences, in its verses and vigils, a luminous vision of human possibility was born: that one could live in the world, fully, joyfully, and yet be free. Today, that vision flickers. But it is not extinguished. It remains in the memory of the Kashmiri Pandits—in their hymns, their breath, their longing. Justice to them is not a regional issue; it is the rekindling of a flame the world once gathered around. Let the temples rise again. Let the texts be studied, not as relics but as living rivers. Let Sharada speak again, through her rightful stewards. Only then can Kashmir reclaim its place—not just in geography—but in the global soul.

Kashmir’s transcendental knowledge is not India’s inheritance alone. It is humanity’s. And its rebirth begins with truth, with justice, and with the return of those who once carried the light. That is the pukar, the call of Amarnath, the abode of the secret of immortality.