By:Dr Zahid

There are moments in civilizational life that do not arrive with thunderclaps of ideology or the pageantry of revolutions. They settle, like dew, unannounced, into the moral grammar of a people. They do not erect institutions, but dismantle hierarchies. They do not prescribe a theology, but perforate the illusion that any one theology is final. Rishism in Kashmir was such a moment. To invoke it today is not to engage in the pieties of nostalgia, but to grope toward a forgotten possibility: that power may be renounced, not seized; that truth may be whispered, not shouted; and that ethics may thrive without spectacle.

To describe Rishism as syncretism is to flatten its defiance into cultural comfort food. Rishism was not a meeting of faiths but a refusal of their certainties. It did not aim for unity; it unmasked the hubris that there is one path to truth. The Rishis were not spiritual entrepreneurs carving a new sect; they were ethical skeptics, demolishing the sanctimony of ritualism and the tyranny of authority—scriptural, political, and intellectual.

Sheikh-ul-Alam, the most luminous of these voices, offers not a theology, but an ethic. His verses sting like moral aphorisms. “An poshe telli yeli wan poshe”—‘If there is sustenance, only then will there be wilderness’—is not just a cry for environmental equilibrium, but an indictment of greed masquerading as progress. His concern was not with salvation in the hereafter but with the hunger, the deceit, the false piety of the here-and-now. Unlike the modern custodians of religion, who trade in grievances and spectacles, Sheikh-ul-Alam demanded an inward revolution—one that has no audience, no reward, and no triumph.

In him, we find what Wittgenstein once demanded of philosophy—that it “leave everything as it is”—but in doing so, expose the moral absurdities we live by. Sheikh’s mysticism is not escapist; it is diagnostic. He strips us of our vanities, and leaves us naked before questions we would rather defer: What is piety that forgets the hungry? What is power that silences dissent? What is knowledge that does not heal?

The modern imagination, conditioned by binaries—secular vs. sacred, resistance vs. submission, identity vs. universality—has no room for the Rishis. For they neither resisted nor submitted; they withdrew. And in that withdrawal was their greatest act of defiance. As Simone Weil wrote, “Real genius is nothing else but the supernatural virtue of humility in the domain of thought.” The Rishis embodied this genius—not as performance, but as presence.

There is something almost Socratic in the way Sheikh-ul-Alam dismantles pretense. His theology is earthbound; his sanctity, unadorned. He sees hypocrisy not as failure but as forgetting. In the words of Nietzsche, “The snake which cannot cast its skin has to die.” The Sheikh urges us to cast away our skins of ritualism, pride, and false knowledge—to be reborn into simplicity.

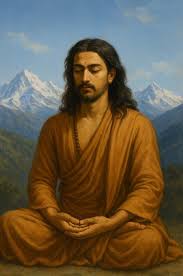

The Rishis were not ascetics fleeing the world; they were ascetics returning to it—transfigured, clarified, softened. Their austerity was not a rejection of life but a deeper embrace of its essence. Their silence was not absence but attention. Their restraint was not withdrawal but a higher form of presence.

And yet, it is precisely this presence that feels so distant now. Our speech has grown louder, our rituals more ornate, our piety more performative. We have learned to display everything and understand nothing. We have, as Heidegger once said, “forgotten the question of Being.” The Rishis never asked us to be religious; they asked us to be real.

“Yi khandar me chu soor,” Sheikh-ul-Alam writes,

“There is melody even in ruins.”

This is not optimism. It is civilizational wisdom. That even in despair, the possibility of grace remains. That what is broken may still speak truth. That what has been lost can yet be remembered. Rishism teaches that restraint is not weakness but the highest form of power. It is a lesson echoed in the Bhagavad Gita when Krishna says:

“He who is not shaken by adversity, who does not hanker after pleasure, and who is free from attachment, fear, and anger—he is a sage of steady wisdom.”

The Rishis lived this wisdom not in grand declarations, but in the smallest acts: in tending to soil, in feeding a stranger, in refusing to hoard. They showed us that civilization does not announce itself in monuments—it reveals itself in mercy.

In Kashmir today, we do not need new ideologies. We need to recover our ethics. Not a blueprint for governance, but a grammar of being. The Rishis do not ask us to return to the past. They ask us to return to ourselves.

“Me chu sokh te saal, me chu wuchhun te haal,”

“I am thirsty and I am the drink, I am the seeing and the seen.”

This is not mysticism. It is the profound realization that the self and the world are not two. That to live rightly is not to conquer the world but to be in the right relation with it.

Let this be Kashmir’s civilizational calling—not to outperform others, but to outgrow the self that clings to fear, vanity, and illusion. The Rishis offered no manifestos, no revolutions, no slogans. They offered something far more enduring: the possibility of wholeness without domination, of clarity without noise, of love without possession.

We may not yet be ready to live as they did. But perhaps we can begin, once more, to listen.