Written By Dr. Zahid

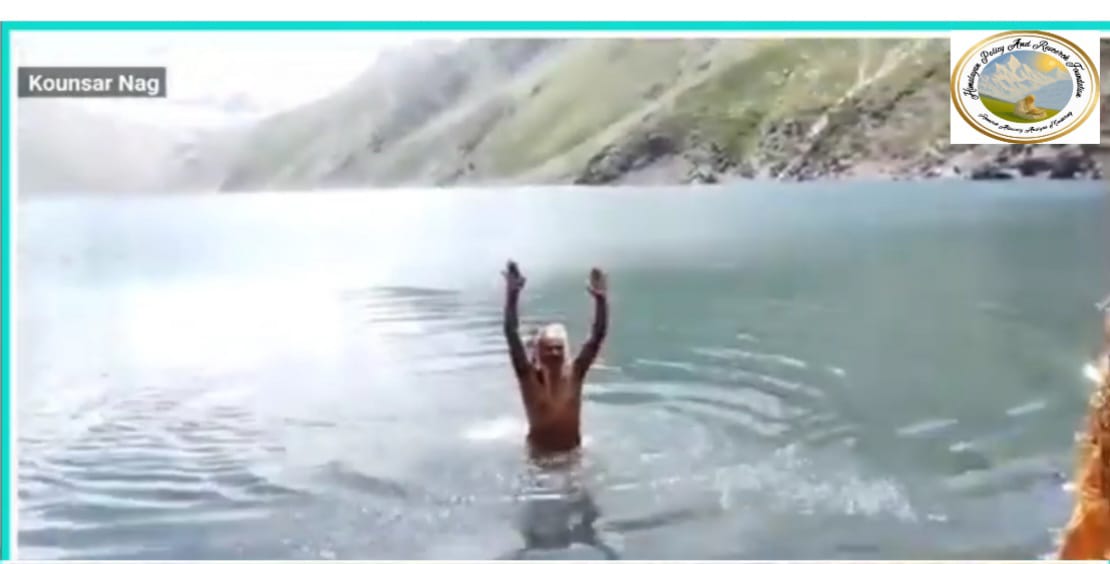

There are places on this earth where time does not pass—it abides. Where the silence is not the absence of sound, but the presence of something deeper than speech. Konsarnag (Vishnu-Padh), a high-altitude oligotrophic lake nestled within the Pir Panjal mountains of Kashmir, is one such space. It is an abode of metaphysical stillness, a site where the restless motion of human history comes to rest, momentarily suspended in a silence deeper than the sum of its myths.

In the words of Utpaladeva, the Kashmiri Shaiva philosopher of the 10th century, “Pratyabhijnanam satyam jnanam anantam”—Recognition is truth, knowledge is infinite. Konsarnag (Vishnu-Padh) is not to be explored, it is to be recognized—not as an object in the world, but as a place that remembers who we were before we became modern.

The Lake as Consciousness Itself

The indigenous metaphysics of Kashmir does not separate the material from the spiritual, the seen from the seer. The lake is not a site in geography, it is a manifestation of consciousness (Cit), expressing itself as water, as wind, as snow. In the framework of Trika Shaivism, the world is not maya in the sense of illusion, but a pulsation (spanda) of divine awareness. Konsarnag is, therefore, not a deviation from the sacred—it is the sacred in its pure, unspeaking form.

This is why the divine truth of Vishnu’s footprint (Vishnu-Padh) is not an embellishment but a philosophical statement. In the Rigveda (I.22.17), Vishnu is said to have taken three steps—across the earth, the atmosphere, and the heavens. These are not steps in space but movements of being. They mark the descent of the infinite into the finite without loss of its infinity. The footprint on Konsarnag, then, is not a trace of the past, but an active signature of the eternal.

The lake holds this paradox in its icy stillness: it is remote, yet intimate; motionless, yet full of life. The Veshaw River that flows from it is not just a source of water, but a thread of continuity between the visible and the invisible, the local and the cosmic.

Zain-ul-Abidin and the Politics of Reverence

When Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin, the beloved Budshah of Kashmir, visited the lake in 1463, he did not arrive as a ruler but as a seeker. His chronicler Srivara captured the moment not as a historical record but as an aesthetic epiphany. The Sultan, we are told, circled the lake in a boat as snow fell, listening to the Gita Govinda, the verses of Krishna’s longing. He built a replica—Zainasara—not to display power, but to invite memory.

This act, far removed from modern statecraft, was an instance of political renunciation—an acknowledgment that certain truths must be approached not through sovereignty, but through submission to wonder. Here, the indigenous understanding of raja dharma finds quiet voice: the king, too, must kneel before that which is beyond measure. “Yatra nari pujyante, ramante tatra devata”, says the Manusmriti—where reverence exists, the divine dwells. So too for landscapes.

Konsarnag is not governed. It governs. Not by force, but by presence. It demands not administration, but reverence.

The Sacred as the Unpossessable

What modernity cannot understand, it seeks to develop. What it cannot measure, it seeks to ignore. Konsarnag resists both. It is immune to commodification precisely because it offers no utility. Its silence cannot be translated into signage. Its waters cannot be reduced to ecosystem services. It is, in the words of Abhinavagupta, “prakasha”—self-luminous. It reveals itself only to those who do not try to extract from it, but to those who are willing to empty themselves before it.

Indigenous philosophy everywhere shares this intuition. The Lakota Sioux say, “The earth does not belong to us. We belong to the earth.” The Adivasi cosmologies of India assert that the forest is not a resource—it is an elder, a being to whom we owe respect. Similarly, Konsarnag is not a lake to be used, it is a presence to be approached with care.

To go there is not to conquer altitude, but to descend into depth. To walk the pilgrimage route from Aharbal through Kungwattan and Mahinag is not an act of fitness, but of recollection—the recovery of a rhythm we once knew: walking not as locomotion, but as offering.

What Remains

Today, the lake remains, even as the pilgrimage falters. Paths overgrow, memories scatter, and yet Konsarnag does not complain. Its dignity lies in its refusal to be urgent. In a world that accelerates toward its own forgetting, the lake waits.

It is the stillness before the word.

It is what remains when kingdoms vanish, when empires rot, when roads are abandoned, when even the rituals fade. It is the kind of silence that contains not emptiness but potential—the seed of a world that might yet remember that not all sacredness lies in text, some of it lies in terrain.

To return to Konsarnag, then, is not to visit a lake. It is to make a choice—to remember a way of being that did not separate knowledge from reverence, philosophy from place, or divinity from the soil. It is a return not to geography, but to grace.

Not to map it.

But to let it unmap you.